Gulladuff: More Heat Than Light

Rusty Nail at Slugger O’Toole

UPDATE: SINN FEIN issues statement calling for a cover-up.

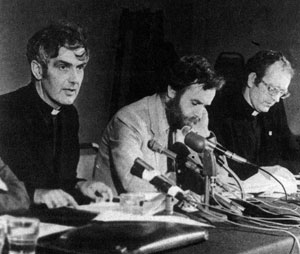

Wednesday night in Gulladuff, South Derry, Gerry Adams, Danny Morrison and Bik McFarlane met with some members of some of the families of the 1981 hunger strikers. Anyone having any hopes of Sinn Fein supporting and honestly participating in a Truth and Reconciliation Commission should just go home now. It was a complete farce from beginning to end. Goons from West Belfast patrolled the parking lot and guarded the door to the community hall. When former Hunger Striker Gerard Hodgins, and Jimmy Dempsey, a former prisoner and father of John Dempsey, the 16 year old boy who died in the riots that occurred at the death of Joe McDonnell, and who is buried in the republican plot alongside McDonnell, along with a representative for the O’Hara and Devine families, asked to participate in the meeting, Danny Morrison forcibly closed the door on them, snarling that they were not wanted, that they had had their chance at the Gasyard Debate to speak to the families and if the families chose not to attend then, it did not mean that he had to allow them into the hall now. When it was pointed out that the representative was there at the request of two of the families, he stated he would go back and ask the families if entry would be permitted. He then locked them out.

Not long after, Bobby Storey, who had nothing to do with the hunger strike, came out and confronted the trio, insulting Gerard Hodgins under his breath by claiming he was in the Continuity IRA and making allegations about the recent break-in at his home. He clapped Dempsey on the back and turned on a sweeter tone, saying he was sorry about his son but he had no right to be there. Hodgins stated he wanted to make clear that he was not in the CIRA, that such allegations were spurious, and was Storey the source of them for the Andersonstown News. Storey rudely snapped, “I’m not talking to you,” and went on attempting to pacify Dempsey. Hodgins responded, “But I am talking to you,” whereby Storey whipped round, pointed his finger directly at Hodgins and said, “See you? I will speak to you at a time and place of my choosing.” This was a clear threat, which Hodgins underlined by asking incredulously, “Are you threatening me?” Realising he had gone too far, Storey made his excuses to Dempsey and was let back into the hall. Dempsey was clearly unhappy at being locked out of a meeting he felt, as his son’s death was a direct result of Joe McDonnells’, he had every right to be at, to ask, did his son have to die? If the outside leadership at the time had accepted the Mountain Climber offer, and Joe McDonnell had not died, nor would have young John Dempsey.

Yet Bobby Storey, a man who had nothing to do with the hunger strike and who had just threatened a hunger striker, had the doors unlocked for him.

And that was only the fireworks outside the meeting. Inside, it got worse.

With an inauspicious start, Adams introduced the meeting referring to “conspiracy theories by anti Sinn Fein elements” and drawing a comparison to conspiracy theories surrounding the death of Michael Collins, one of which alleges he was set up and shot by his own IRA men.

All the inconsistencies in the press to date were only amplified at the meeting. Attempts to clarify points or challenge previous statements were met with indignant fits of pique, such as Morrison claiming he would never sit in the same room with Richard O’Rawe, “the man who accused me of murdering 6 hunger strikers!”, or Gerry Adams repeatedly asking, “Do you think I am telling the truth, yes or no?”

Bik McFarlane also kept to the discredited nonsense that it was the hunger strikers who rejected the offer, despite evidence that the hunger strikers were never told the details of the offer. He and Morrison claimed that all the hunger strikers (including Lynch and Devine) were told about the Mountain Climber offer and had refused, saying it was not enough. McFarlane then denied he ever had the the “Tá go leor ann” conversation with O’Rawe based on that claim, saying, “How could I? After hearing the men reject the offer put to them?” This notion does not jibe with any of the historical records and accounts of that time period.

Bik McFarlane claimed that he was always saying “I agree with you” in Irish to Richard, in a pathetic attempt to explain away the prisoners coming forward who overheard the conversation between himself and O’Rawe accepting the Mountain Climber offer. He was explaining that the prisoners who heard that conversation were mixing up the numerous conversations he had with O’Rawe in which he agreed with what O’Rawe was saying. This of course moves further still from his starting position of never having had any such conversation with O’Rawe, to now having had so many, he and other prisoners would be unable to keep track of them.

The ICJP and Mountain Climber offers were conflated in an attempt to obscure the outside rejection of the Mountain Climber offer. PRO statements, statements which were written at the behest of Adams, were repeatedly presented as if they reflected the private comms between the prison leadership and the outside. None of the private comms referring to the Mountain Climber, which O’Rawe had given Adams in 1986, were produced.

O’Rawe was demonised in the meeting, called a liar, painted as the villain and ascribed nefarious motives for pursuing the truth. Some families’ representatives were characterised as ‘anti-GFA’ and those who had attended the Gasyard debate, many of whom were former blanketmen, were derided as ‘yahoos’. A dubious motion was attempted to get the families to agree to a joint statement that would say they were all agreed any probing into the past should cease. They ‘had enough’, ‘old wounds had opened up’, and O’Rawe ‘should stop’,’ he was ‘only after money for books’; Danny Morrison fanned the flames of the attacks on O’Rawe’s character, keeping them going whenever they appeared to peter out. He mentioned O’Rawe’s taking him to court ‘over things I said during an RTE interview’, described how no matter how often he would meet O’Rawe, he never mentioned the relevations. A meeting on the hunger strike was turned into a manipulative back stabbing session. The Sunday Times and Republican Network for Unity were in for kickings as well. The proposed joint statement was objected to and not supported by all. A suggestion that the families meet with O’Rawe and others was knocked back. It was put forward that one of the families approach O’Rawe to tell him to ‘back off’ and ask for a response. No motions proposed were passed; the meeting was becoming very emotional and many family members were close to tears.

Adams, McFarlane and Morrison were asked would they cooperate with an independent inquiry; the answer was a resounding “NO.”

After an hour and a half of hectoring, emotional manipulation, browbeating and more lies, Mickey Og Devine left early, visibly upset. He was disgusted with what he felt was nothing more than a sham, and with all the shouting and deflection when points were raised that challenged the platform. Other family members were also emotionally distraught when the meeting ended not long after he left.

Last weekend in New York, Gerry Adams waxed nostalgic about the peace process, noting how long it took to get from the start of the process to where Sinn Fein are today. He made observations about all the people – ‘the naysayers and begrudgers’ – who were against the peace process, who did not think it would work, and who did not want Sinn Fein to participate in such. Yet, he proudly claimed, Sinn Fein persevered.

Some Slugger readers will recall, in 1996, prior to the Good Friday negotiations, the image of Adams and McGuinness standing outside locked gates, begging civil servants for access to the British talks going on without them. Now Sinn Fein locks out republicans from their ‘private’ Widgery on their own actions during the Hunger Strike. A widgery in which they absolve themselves of any and all wrongdoing and condemn those who seek only the truth, putting figurative nailbombs into the pockets of anyone who dared challenge them.

The hypocrisy of allowing Bobby Storey, party enforcer, to stand menacingly at the back of the hall with his arms folded, glaring at anyone who didn’t pay homage to Dear Leader, while barring entry to a former hunger striker, the father of a young Fian killed as a result of Joe McDonnell’s death, and representatives requested by families is staggering.

However long it takes from being locked out of a SF widgery until finally achieving a full independent inquiry, with the ability to challenge all views openly and forthrightly in order to ascertain what exactly did happen and why, with or without an official Truth and Reconciliation Commission, those seeking the truth of what happened in July 1981, will persevere, just as Sinn Fein did, despite the naysayers and begrudgers who would rather bury the truth, or present a whitewash as fait accompli. No one is asking for another Bloody Sunday type inquiry – but a Widgery is unacceptable.

In using the families to hide behind the skirts of, it must be remembered that Sinn Fein has not had a problem with disrespecting and going against families of hunger strikers’ wishes when it suits them. Slugger has already noted the Sands family withdrawal of support for the Bobby Sands Trust, of which Morrison, McFarlane and Adams are on the board, because they were deeply unhappy with what they felt was the abuse of their relative. In addition, the Sands family were also vocal about their displeasure with the Denis O’Hearn biography of Bobby Sands, “Nothing But An Unfinished Song”. This did not, however, stop Sinn Fein, through Eoin O’Broin’s Left Republican Review, from publishing the book in conjunction with Pluto Press, nor launching the book across the country and supporting the children’s edition of the biography, which was co-written with Laurence McKeown. Sinn Fein was so ecstatic about that book they wanted it introduced into school curriculum. The Sands’ family position on the book, and indeed, the gross abuse of Bobby Sands’ image by the party, means absolutely nothing to Sinn Fein.

If we support the right of O’Hearn, as a historian, to write a biography of a noted historical figure, and the right of former prisoners McKeown and Elliott to contribute to an adaptation for children, while also endorsing its use in schools, despite the express wishes of the family; then it follows that we must support O’Rawe’s book as well.

This therefore becomes an issue of freedom of speech; for if families are to hold history hostage to their emotions, nothing would be written. If families are to be manipulated by politicians who wish to bury the truth of history, and people are then expected, via emotional blackmail, to defer to “the families’ wishes”, nothing would be written but the politicians’ lies. Families may express their disapproval but that will not and should not stop history from being probed, challenged, written, and read.

Clearly, ‘private’ meetings are not sufficient to address public concerns about important issues such as the hunger strikes, which had a massive impact on society beyond a handful of family members. Enough information and evidence is now out in the public domain that needs answered elsewhere from Diplock courts. Blanketmen have the right to ask their leaders of the time for a public and truthful accounting of what they did and why, without it being reduced to a browbeating exercise in deflection. The republican community at large is deeply scarred by the hunger strike and they too deserve the truth. Beyond that, the unionist community also has a right to know was the hunger strike prolonged for the promotion of Sinn Fein, as that impacts their own history greatly as well. The truth can’t be disappeared, no matter how many attempts to bury it are made.

Somehow, the bodies keep being found.

Appendix:

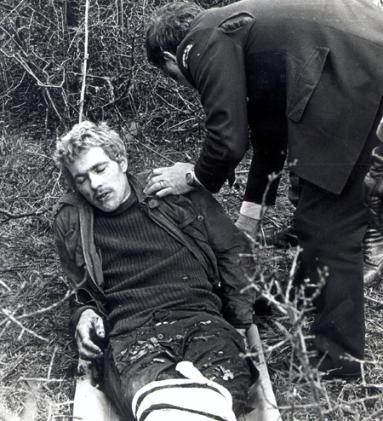

Father and son Jimmy and John Dempsey, as written about by Gerry Adams. Jimmy Dempsey was denied entry and locked out of the meeting in Gulladuff.

An Phoblacht, 15 May 2003

Remembering Fian John Dempsey

Within hours of the death on hunger strike of Joe McDonnell, the British Army shot dead 16-year-old Fian John Dempsey. He and two comrades were on active service when they come under fire from a squad of British soldiers at the Falls Road bus depot in Belfast.

John Dempsey died later in the Royal Victoria Hospital. Last week, on Monday 5 May, republicans from the Turf Lodge area of West Belfast unveiled a plaque at the Falls Bus Depot near the spot where he was killed.

As a tribute to the young republican, we reprint an edited version of an article written by Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams, using the pen name Brownie, in which he outlined the political and social conditions that influenced the thinking of young nationalists and led them into the struggle for national liberation.

Until the morning of last Wednesday week, Fian John Dempsey, aged 16, lived in one of the grey houses which sprawl on either side of the Monagh Road in Turf Lodge.

His family, a week after his death, are now like so many other families, trying to pick up the pieces – in the heart-rending vacuum which is always created by sudden death, especially by the death of one so young and cheerful as John.

At the wake on Thursday week he looks only twelve years old, his body laid in an open coffin flanked by a guard of honour from Na Fianna Éireann.

Hardened by many funerals, by too many sudden deaths, yet one is riveted to the spot unable to grasp the logic, the divine wisdom, the insanity, which tightened a British soldier’s trigger finger and produced yet another corpse.

“He’s so young, ” exclaimed those who call to pay their respects. “Jesus, he’s only a child.”

All night, neighbours, friends and relatives call. All with the same reaction.

But young people call also, shifting uncomfortably in adult company, but strangely unshocked – not visibly at any rate – by what they see in the sad living room of the Dempsey home.

Just a tightening of young faces as they gaze silently at John’s remains, a hardening of eyes, and then silently out again to stand in small groups at the street corner. None of the awkward handshakes and mumbled “I’m sorry for your troubles”.

They understand better than most the logic which directed the British Army rifle at John, and, having understood, they pay their respects and move outside – to wait.

John’s mother, Theresa, sits comforted by friends, while her husband Jimmy stands, a gaunt figure at the head of his son’s coffin, gently stroking John’s head. Jimmy shakes hands with Dal Delaney – both fathers of dead patriots (the latter of Dee Delaney killed in a premature bomb explosion in Belfast in January 1980).

Many of Jimmy’s prison comrades come to the house. He spent six years in Long Kesh as a political prisoner, and soon talk turns to the Kesh, but not like at an adult wake where ‘craic’ flows non-stop.

At least, not in the living room, where the youthful figure in the coffin brings one sharply back from what has passed to what lies ahead, from what has been done, to what still remains to be done.

The next morning, the slow sad procession to the chapel on a bright warm summer morning; and after Mass, the girl piper heralding our passing as we make our way, once again, to Milltown. Down from the heights of Turf Lodge, past the spot where John was murdered, and by the British Army barracks, through the open gates of the cemetery, to the republican plot, where two open graves – one for Joe McDonnell – await our arrival.

John left school at Easter. He played hurling and football for Gort Na Mona and soccer for Corpus Christi, and like his father and his many uncles he was a keep fit enthusiast with an interest in body building.

He joined Na Fianna Éireann in October 1980 and like many young people from Turf Lodge, was subjected to regular harassment by British soldiers.

Wreaths are laid before we leave for Lenadoon and the funeral of Joe McDonnell.

John Dempsey’s funeral, a smaller and in many ways a sadder ceremony than Joe’s, is a stark reminder that for the first time in contemporary Irish history, the struggle has crossed the generation gap.

When Joe McDonnell was first interned in 1972, John Dempsey was a mere seven years old. Yet they were to die and be buried in the same republican plot, within hours of each other, in the service of a common cause and against the same enemy.

As Jimmy Dempsey said of his son, “John has joined the elite. He died for the freedom of his country.”

(A tribute by Brownie) first published in AP/RN 18/7/81

Marcella Sands on record about Denis O’Hearn’s biography of her brother, Bobby:

In response to an article headlined ‘New Book is First Study of Bobby Sands’, which appeared in a recent edition of the Andersonstown News, I wish to put the record straight.

According to the article, the author of the book, Denis O’Hearn, “thanks the hunger striker’s sister Marcella for her help with the book.” This suggests that I had “helped” or participated in some way in the compilation of this book and, therefore, endorsed it. This is misleading and untrue.

I wish to state categorically that neither I, nor any of my family, helped Mr O’Hearn with his book in any way, nor does my family endorse the book. Indeed, the opposite would be the case as his book contains numerous factual inaccuracies.

Denis O’Hearn’s acknowledgment of the family’s position:

[Part of the article could give] the mistaken idea that the Sands family participated in the research for the book. This is not so. I met Marcella Sands when I was beginning my research and she told me that the family did not feel that they could participate because they were writing their own memoirs and it would create a conflict of interest if they also helped me. I respected their decision and on numerous occasions when people asked me, I made it clear that Bobby’s immediate family was not participating.

In a ‘special investigation’ this week The Irish News has rehashed the claim made by Richard O’Rawe in 2005 that a deal was on offer from the British government to resolve the 1981 Hunger Strike and that this alleged deal was scuppered by the leadership of the Republican Movement.

In a ‘special investigation’ this week The Irish News has rehashed the claim made by Richard O’Rawe in 2005 that a deal was on offer from the British government to resolve the 1981 Hunger Strike and that this alleged deal was scuppered by the leadership of the Republican Movement. LEADING Belfast republican Padraic Wilson is to speak at a Belfast Hunger Strike Commemoration night in the Whiterock Leisure Centre on Sunday, 16 August.

LEADING Belfast republican Padraic Wilson is to speak at a Belfast Hunger Strike Commemoration night in the Whiterock Leisure Centre on Sunday, 16 August. After being released in 1999 he became active again in Sinn Féin and currently holds the position of Director of International Affairs.

After being released in 1999 he became active again in Sinn Féin and currently holds the position of Director of International Affairs.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.