Oct 8, 2009 1

Gerry Adams: The Irish News and Garret FitzGerald’s ‘new memory’ about 1981 H-Blocks Hunger Strike deal

The Irish News and Garret FitzGerald’s ‘new memory’ about 1981 H-Blocks Hunger Strike deal

By Gerry Adams

An Phoblacht

8 October, 2009

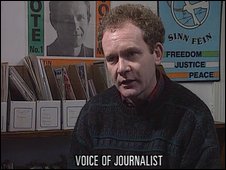

Sinn Fein asked The Irish News for a full right of reply and the newspaper agreed. When the response from Gerry Adams was harshly critical of the Irish News itself, the article was blocked. An Phoblacht carries the article below. We are waiting for the Irish News to do the same.

TWENTY-EIGHT years ago, ten Irish republicans died over a seven-month period on hunger strike, after women in Armagh Prison and men in the H-Blocks (and several men ‘on-the-blanket’ in Crumlin Road Jail) had endured five years of British Government-sanctioned brutality.

The reason for their suffering was that, in 1976, the British Government reneged on a 1972 agreement over political status (“special category status”) for prisoners which had actually brought relative peace to the jails.

You would not know that from reading this series in The Irish News.

Nor would you know from reading Garret FitzGerald’s newly-found ‘memory’ of 1981 that in his 1991 memoir he wrote:

“My meetings with the relatives came to an end on 6 August when some of them attempted to ‘sit in’ in the Government anteroom, where I had met them on such occasions, after a stormy discussion during which I had once again refused to take the kind of action some of them had been pressing on me.”

This came after a Garda riot squad attacked and hospitalised scores of prisoners’ supporters outside the British Embassy in Dublin only days after the death of Joe McDonnell.

It is clear from FitzGerald’s interview and from his previous writing that his main concern – before, during and after 1981 – was that the British Government might be talking to republicans and that this should stop.

With Margaret Thatcher he embarked on the most intense round of repression in the period after 1985. Following the Anglo-Irish Agreement of that year, the Irish Government supported an intensification of British efforts to destroy border crossings and roads and remained mute over evidence of mounting collusion between British forces and unionist paramilitaries.

The same FitzGerald was portrayed as a great liberal, yet every government which he led or in which he served renewed the state broadcasting censorship of Sinn Féin. This denial of information and closing down of dialogue subverted the rights of republicans. It also helped prolong the conflict.

The Irish News played an equally reprehensible role.

As far as I am concerned, this newspaper is ‘a player’ in these attacks on Sinn Féin. Oh, but had The Irish News given a series to the Hunger Strikers when they were alive! Instead, at the same time as The Irish News decided to publish death notices for British state forces, this paper refused to publish a death notice from the Sands family because it carried the words “In memory of our son and brother, IRA Volunteer Bobby Sands MP”.

The men who died on hunger strike from the IRA and INLA were not dupes. They had fought the British and knew how bitter and cruel an enemy its forces could be, in the city, in the countryside, in the centres of interrogation and in the courts.

But you would not know that from reading this series in The Irish News.

The prisoners – our comrades, our brothers and sisters – resisted the British in jail every day, in solitary confinement, when being beaten during wing shifts, during internal searches and the forced scrubbings.

The Hunger Strike did not arise out of a vacuum but as a consequence of frustration, a failure of their incredible sacrifices and the activism of supporters to break the deadlock, to put pressure on the British internationally and, through the Irish Establishment, including the Dublin Government, the SDLP and sections of the Catholic hierarchy – although you would not know that from reading this series in The Irish News.

In December 1980, the republican leadership on the outside was in contact with the British, who claimed they were interested in a settlement. But before a document outlining a promised, allegedly liberal regime arrived in the jail, the Hunger Strike was called off by Brendan Hughes to save the life of the late Seán McKenna. The British, or sections of them, interpreted this as weakness. The prisoners ended their fast before a formal ‘signing off’. And the British then refused to implement the spirit of the document and reneged on the integrity of our exchanges.

Their intransigence triggered a second hunger strike in which there was overwhelming suspicion of British motives among the Hunger Strikers, the other political prisoners, and their families and supporters on the outside.

This was the prisoners’ mindset on 5 July, 1981, after four of their comrades had already died and when Danny Morrison visited the IRA and INLA Hunger Strikers to tell them that contact had been re-established and that the British were making an offer.

While this verbal message fell well short of their demands, they nevertheless wanted an accredited British official to come in and explain this position to them, which is entirely understandable given the British Government’s record.

Six times before the death of Joe McDonnell, the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace (ICJP), which was engaged in parallel discussions with the British, asked the British to send an official into the jail to explain what it was offering, and six times the British refused.

After the death of Joe McDonnell, the ICJP condemned the British for failing to honour undertakings and for “clawing back” concessions.

Ex-prisoner Richard O’Rawe, who never left his cell, never met the Hunger Strikers in the prison hospital, never met the governor, never met the ICJP or Da nny Morrison during the Hunger Strike, and who never raised this issue before serialising his book in that well-known Irish republican propaganda organ, The Sunday Times, said, in a statement in 1981:

“The British Government’s hypocrisy and their refusal to act in a responsible manner are completely to blame for the death of Joe McDonnell.”

But you would not know that from reading this series in The Irish News.

Republicans involved in the 1981 Hunger Strike met with the families a few months ago. Their emotional distress and ongoing pain was palpable. They were intimately involved at the time on an hour-by-hour basis and know exactly where their sons and brothers stood in relation to the struggle with the British Government.

They know who was trying to do their best for them and who was trying to sell their sacrifices short.

More importantly, they know the mind of their loved ones. That, for me, is what shone through at that meeting. The families knew their brothers, husbands, fathers. They knew they weren’t dupes. They knew they weren’t stupid. They knew they were brave, beyond words, and they were clear about what was happening.

All of the family members, who spoke, with the exception of Tony O’Hara, expressed deep anger and frustration at the efforts to denigrate and defile the memory of their loved ones. In a statement they said:

“We are clear that it was the British Government which refused to negotiate and refused to concede the prisoners’ just demands.”

But you would not know that from reading this series in The Irish News.

Stature of ten men unassailed

Stature of ten men unassailed

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.