Never-before-seen 1981 hunger strike documents disclosed

01 September 2010

By William Allen

Londonderry Sentinel

DOCUMENTS kept secret since 1981 have revealed a fascinating picture of how Margaret Thatcher’s Government dealt with the IRA hunger strike.

The documents released by the Northern Ireland Office show how the Government was determined to maintain a firm stance in public while trying to come to an arrangement that the IRA would agree to through secret contacts.

The request for the documents was made under the Freedom of Information Act by the Sentinel amid claims that several of the hunger strikers were sacrificed to boost the republican movement’s electoral strategy and that an acceptable offer was made but the hunger strikers were not told by the IRA.

The papers, released 15 months after being requested, show the Government was working on a number of levels, with organisations such as the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace (ICJP), while also using a secret conduit directly to the IRA – believed to be the Mountain Climber initiative.

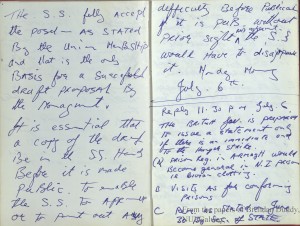

Taken at face value, there is no evidence on whether protestors wanted to agree a deal but were over-ruled by IRA leaders. But the documents do show offers were made secretly to the IRA rather than directly to the hunger strikers, and illustrate the central role played by Brendan McFarlane, the Provisional IRA leader in the jail.

Chance to clarify

And they also show that, less than two weeks before the death of Dungiven INLA man, Kevin Lynch, the hunger strikers were offered a chance to clarify the latest position in front of relatives and clergy, but the prisoners’ insistence that they would only meet in McFarlane’s presence was rejected by the Northern Ireland Office officials, who saw him as intransigent.

The 32 newly released documents, combined with a number that were previously released, offer an amazing insight into the Government’s dealings with a range of agencies, including the Dublin Government, Irish Commission for Justice and Peace, the Vatican, and Catholic Church leaders in England as well as Ireland. They also show how the Government was involved in backdoor approaches and attempts to find a formula and form of words that would allow a solution to be choreographed – a forerunner to the way the Peace Process unfolded in the 1990s.

The documents show that the Government consistently believed the prisoners were acting under orders and that McFarlane would not consider anything short of negotiating the “five demands”.

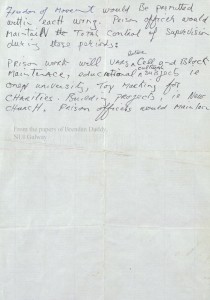

These demands were: the right not to wear a prison uniform; the right not to do prison work; the right of free association with other prisoners, and to organise educational and recreational pursuits; the right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week; full restoration of remission lost through the protest.

The documents show how the Government’s position shifted from its early belief that it was involved in a stand-off that there could be no compromise on, though it was consistent in demanding an end to the protest before any public moves would be made on its part. And it showed how the Government believed it was also fighting a propaganda battle.

Holy See

A telegram to the Holy See in April 1981 insists that the Government could not back down and regretted that the Pope’s personal plea to the hunger strikers to end the protest failed.

As the death of the first hunger striker, Bobby Sands drew near, a telegram to the NIO mentioned talks with an Irish government representative, saying that: “Nally agreed that while there was a concern in the south over the consequences of Sand’s death, support for the hunger strikers was very limited. However, Sand’s death, particularly if followed by Hughes, could change things.”

The documents show that a press release had been prepared before Sands died, with the time and date, and the number of days he had refused food to be inserted after his death.

But the hardline, public approach was not being followed through in private by July.

An extract from a letter – previously released to the Sunday Times – dated July 8, from 10 Downing Street to the NIO said the PM had met the Secretary of State Humphrey Atkins after the message that the PM had approved had been communicated to the Provisional IRA. It said the IRA originally did not regard it as satisfactory but when it was made clear that this ended the initiative, this “had produced a rapid reaction which suggested that it was not the content of the message which they had objected to but only its tone”.

The Secretary of State, “had concluded that we should communicate with the PIRA over night a draft statement enlarging upon the message of the previous evening but in no way whatever departing from its substance. If the PIRA accepted the draft statement and ordered the hunger strikers to end their protest the statement would be issued immediately. If they did not, this statement would not be put out but instead an alternative statement reiterating the Government’s position as he had set it out in his statement of 30 June and responding to the discussions with the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace would be issued. If there was any leak about the process of communication with PIRA, his office would deny it.”

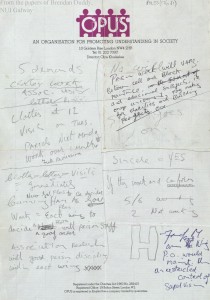

Documents show the Government took advice from experts on what way a statement could be worded so that the IRA would accept it.

A later telegram from the NIO said a statement had been read adding: “we await provo reactions (we would be willing to allow them a sight of the document just before it is given to the prisoners and released to the press). It has been made clear (as the draft itself states) that it is not a basis for negotiation.”

Communications between the Secretary of State’s office and the ICJP, including one on July 6, suggest the body believed a statement “together with clarifications received” encouraged it to continue its efforts, with the NIO saying it did not want the public to know yet about a letter to the ICJP, as “public knowledge of the fact that they have had a letter will bring immediate pressure on us and them to disclose the contents – just now this might not be helpful”. It added the ICJP had been told it would have to become public at some point, otherwise the Government would be accused of “secret deals” but that the timing and terms of the release would need to be agreed.

The clarifications included issues like association, prison work, remission and clothing.

Another document records a statement read to prisoners from the Secretary of State, who said no moves could be made under the duress of a hunger strike but “making sure that the protestors were aware of what was available”.

It said: “Little expansion of association was contemplated but the suggestion of association of adjacent wings (made by the ICJP) was taken on board. On clothing the ‘possibility of further development’ had not been ruled out. On work, no-one would be excluded but the commitment was given to add to the range of activities, including examination of the ICJP’s suggestions. No more than the existing 1/5 restoration of lost remission to ex-protestors was promised.”

It says there was no reaction shown from the prisoners though Michael Devine and Thomas McElwee asked if officials could come and discuss the document after they had read it.

It added: “The prisoners were given an opportunity to discuss the document among themselves and also saw McFarlane for a time. Lynch and Doherty – the 2 most determined strikers – said afterwards that there was nothing in it for them.”

The undated document carries details of an IRA statement said to have been smuggled from the prison on July 8, saying that Joe McDonnell need not have died and describing Mr Atkins’ statement that day as “ambiguous and self-gratifying”.

A telegram sent by Lord Carrington on July 15 said that Mr Atkins had given instructions that a NIO official should go to the Maze to explain the Government’s “ICRC” (International Committee of the Red Cross) initiative to the hunger-strikers, and answer any questions about Mr Atkins’ statement of July 8.

A note dated July 16, says that Mr (John) Blelloch had been in to see the hunger strikers on July 15: “All 8 were there. Doherty could not read but appeared to comprehend generally. The Governor delivered the statement. The strikers listened closely…

“The prisoners then asked to see McFarlane. The Governor agreed to a limited session. Mr Blelloch asked the prisoners if they had reflected on the SoS’s statement of 8 July. They said they had and had one or two points; but they didn’t pursue this and seemed much more interested in ICRC.

“The Governor and Mr Blelloch then left and McFarlane was fetched. The Governor’s ‘feel’ was that the atmosphere was one of ‘deathly calm’. They realized the seriousness of their situation but were unlikely to act without PSF orders. They would probably decide nothing that night but want to hear the radio and possibly receive “messages” via visitors.

“At 8.45pm Mr Blelloch phoned to say that McFarlane had returned to his cell and the hunger-strikers had dispersed without requesting a further meeting.”

Secret channel

Another (previously released) document shows that Margaret Thatcher wanted to make another approach to the IRA through the secret channel but changed her mind after it was put to her that there was a risk of the offer becoming public.

A letter dated July 18 from Downing Street to the NIO said that Philip Woodfield had come to brief the PM on the situation and that after the latest IRA statement Mr Atkins felt the need to respond either with a statement or by sending in an official to clarify the position again.

“The official would set out to the hunger strikers what would be on offer if they abandoned their protest. He would do so along the lines discussed with the Prime Minister last week. He would say that the prisoners would be allowed their own clothes, as was already the case in Armagh prison, provided these clothes were approved by the prison authorities. (This would apply in all prisons in Northern Ireland).

“He would set out the position on association; on parcels and letters; on remission; and on work. On this last point he would make it clear that the prisoners would, as before, have to do the basic work necessary to keep the prison going: there were tasks which the prison staff could in no circumstances be expected to do. But insofar as work in the prison shops was concerned, it would be implicit that the prisoners would be expected to do this but that if they refused to do it they would be punished by loss of remission, or some similar penalty, rather than more severely…

“The statement would be spelling out what had been implicit in the Government’s public statement and explicit in earlier communications.”

It said the PM agreed that one more effort should be made to explain the situation to the hunger strikers, but then, following further discussions “it was drawn to the Prime Minister’s attention that any approach of the kind outlined above to the hunger strikers would inevitably become public whether or not it succeeded, the Prime Minister reviewed the proposal on the telephone with the Secretary of State and decided the dangers in taking an initiative would be so great that she was not prepared to risk them.

“The official who went in to the prison could repeat the Government’s public position but could go no futher.”

Further documents show the “network of contacts” was being followed up.

There are two documents recording details of a visit by Mr Belloch and Mr Blackwell to the prison on July 20, a week after the death of Martin Hurson, the sixth of ten men to die.

Both said the visit was prompted by a call from Kevin Lynch’s priest who said Lynch and relatives of Kieran Doherty wanted an NIO official to visit the Maze to clarify the Government statement of July 19. Both hunger strikers denied asking for a visit but “were content for an official to see the group of hunger strikers”.

Mr Blelloch gave relatives an outline of the Government’s position. The assistant governor visited each of the hunger strikers to tell them of the presence of an NIO official but all said they would only meet him as a group and “all but Lynch had said that McFarlane must be present”.

It added: “Mr Blelloch first spoke to the families and explained the position with regard to McFarlane. He made clear that he would speak to the hunger strikers as individuals or as a group and in front of relatives or priests if they wished…We then visited each hunger striker in turn and Mr Blelloch explained that he was an official from the NIO and he was there to see if he could help. In each case the hunger striker’s response was the same – they would only see him in a group and McFarlane must be present. Even Lynch who had not previously mentioned McFarlane now did so…It was decided not to approach the other three hunger strikers in H.3 since that was McFarlane’s block and they were most unlikely to agree to a meeting without his presence.”

The other document on the visit backs this up, saying: “Lynch had said he would like an official to see him and the group and Doherty had said he would like an official to see him and the group and McFarlane.”

Mr Blelloch and Mr Blackwell arrived: “The prison officer said that all five hunger strikers in the prison hospital (except Lynch) were insisting on McFarlane being present.” However it said that when they spoke to Lynch, he now also insisted that McFarlane be present so no-one took up the offer of a meeting. Officials were told he and others were too weak and needed a spokesman.

It adds under the heading “Background briefing”: “The reason they did not wish to take up the offer was because they wished to insist on the presence of McFarlane who had made clear that all he was interested in was tearing up the Government’s statements and negotiating the ‘5 demands’.”

All 32 of the newly released documents will be published on the Sentinel’s website, www.londonderrysentinel.co.uk, as well as a number of those supplied to the Sentinel which had previously been disclosed.

Sourced from the Londonderry Sentinel

![Pol35_0166_0001 Send on 5 of July Clothes = after lunch Tomorrow and before the the afternoon visit as a man is given his clothes He clears out his own cell pending the resolution of the work issue which will be worked out [garbled] as soon as the clothes are and no later than 1 month. Visits = [garbled] on Tuesday. Hunger strikers + some others H.S. to end 4 hrs after clothes + work has been resolved.](http://www.longkesh.info/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Pol35_0166_0001-300x228.jpg)

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.