UPDATED 25 Nov 2011 – Brendan Duddy’s Mountain Climber notes added; quote from John Blelloch

UPDATED 11 July 2009 – Excerpts from Biting at the Grave added

Merged Timeline – Joe McDonnell’s death

Please note this timeline is by no means definitive and is subject to revision as more sources are added and/or more evidence and information comes to light. This timeline is a verbatim compilation of various sources in a chronological order and is open to interpretation.

Sources: Danny Morrison, Garret Fitzgerald, Brendan Duddy, John Blelloch, British Government documents, Ten Men Dead, Before the Dawn, Biting at the Grave, INLA Deadly Divisions, Blanketmen, Irish News, Belfast Telegraph, eyewitness accounts.

KEY:

DM = Danny Morrison

GF = Garret Fitzgerald

Other sources are noted in text.

29 June

DM: Four hunger strikers have already died – Bobby Sands on day 66, Francis Hughes on day 59, Raymond McCreesh and Patsy O’Hara on day 61 of their hunger strike.

DM: Joe McDonnell is on day 52 without food. Secretary of State, Humphrey Atkins reaffirms that political status will not be granted and that implementing changes in the areas of work, clothing and association present ‘great difficulty’ and would only encourage the prisoners to believe that they could achieve status through “the so-called ‘five demands’”.

30 June

GF: “The IRA reaction, allegedly on behalf of the prisoners, had been to describe this response as ‘arrogant’. Nevertheless the Commission for Justice and Peace saw the British statement as encouraging – as did we – and sought further clarification. Our information from the prison was that, despite the IRA statement purporting to speak for them, the prisoners wanted the commission to continue its involvement. We were also aware that the relatives of the prisoners on hunger strike were becoming increasingly restive at the IRA’s intransigent approach.”

1 July

GF: “On 1 July Michael O’Leary and I communicated our view on these points to the British Ambassador and urged that the NIO meet the commission again and allow the commission to meet the prisoners. We also warned against any policy of brinkmanship, which – especially in the view of the nearness to death of one hunger striker, Joe McDonnell – could harden attitudes, including in particular the attitudes of the relatives, who had the power to influence developments. That night I rang Margaret Thatcher to make these points directly to her.”

3 July

DM: Irish Commission for Justice and Peace [ICJP] has eight-hour meeting with Michael Alison, prisons minister.

GF: Garret Fitzgerald meets with relatives of the prisoners/hunger strikers:

“This meeting on 3 July was, as I had expected, intensely distressing, but it enabled me to see for myself that while there were those among them who took a straight IRA line, most of them were indeed primarily concerned to end the hunger strike.”

4 July

DM: ICJP again meets Alison who gives its representatives permission to meet the eight hunger strikers in prison hospital. They are shocked at the condition of Joe McDonnell. Prisoners later issue statement saying British government could settle the hunger strike without any departure from ‘principle’ by extending prison reforms to the entire prison population. ICJP tells prisoners’ families that they are ‘hopeful’ but that prisoners deeply distrust the authorities.

DM: British government representative (codenamed ‘Mountain Climber’) secretly contacts republican leadership by ‘back channel’. Insists on strict confidentiality.

GF: “The Minister of State at the NIO, Michael Allison, met the commission again. He gave the impression that he wanted to be more conciliatory, but referred to ‘the lady behind the veil’, namely the Prime Minister. As we had proposed, he cleared a visit by the Commission for Justice and Peace to the prisoners, who then issued a statement that, as we had thought likely, was much more conciliatory than the one published by the IRA on their behalf three days earlier. They said they were not looking for any special privileges as against other prisoners, and that the British government could meet their requirements without any sacrifice of principle. It looked as if the commission would now be able to resolve the dispute with Michael Allison, who seemed close to accepting their proposals.”

GF: “Following the conciliatory statement by the prisoners, direct contact had been made with the IRA by an agent of the British government, through an intermediary. Disastrously, his proposals, while close to what the prisoners and Allison, through the commission, were near to agreeing, went further in one respect. Not unnaturally the IRA preferred this somewhat wider offer, and above all the opportunity to be directly involved in discussions with the British government.”

Padraig O’Malley, Biting at the Grave, pg 90-92: “Both sides met again on 4 July for what the Commission members felt was a pro-forma exercise. Within minutes of the meeting’s beginning, however, Alison did a complete about-face. If the hunger strikes were to end, he told the Commission, the government would not appear to be acting under duress, in which case all prisoners would be allowed to wear their own clothes. Own clothing as a right, not a privilege, Hugh Logue asked. Own clothing as a right, Alison replied.”

“After the meeting with Alison the Commission was given permission to go immediately to the Maze/Long Kesh prison. When they arrived, they were brought to the hospital wing […] The eight hunger strikers sat on one side of a table on which jugs of water had been placed; the five commissioners sat opposite them.”

“For the next two hours the two sides went over the proposals the Commission had hammered out with Alison and which it now thought were on offer. Prisoners would be allowed to wear their own clothes at all times as a matter of right, not privilege; association would be improved by allowing movement by all prisoners during daily exercise time between the yard blocks of every two adjacent wings within each block and between the recreation rooms of the two adjacent wings in each block during the daily recreational period; the definition of work would be expanded to ensure every prisoner the widest choice of activities – for example, prisoners with levels of expertise in crafts of the arts could teach these skills to other prisoners as part of their work schedules, prisoners would be allowed to perform work for a range of charitable or voluntary bodies, and such work could even include the building of a church “or equivalent facilities for religious worship within the prison”.”

5 July

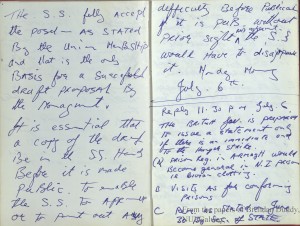

Brendan Duddy’s Mountain Climber notes:

Send on 5 of July

Clothes = after lunch

Tomorrow

and before the the afternoon visit

as a man is given his clothes

He clears out his own cell pending the resolution of the work issue which will be worked out [garbled] as soon as the clothes are and no later than 1 month.

Visits = [garbled] on Tuesday. Hunger strikers + some others

H.S. to end 4 hrs after clothes + work has been resolved.

Padraig O’Malley, Biting at the Grave, pg 96:

“…Danny Morrison was allowed to go into the Maze/Long Kesh to see the hunger strikers on the morning of 5 July…to apprise them of what was going on, although he did not go into detail. Morrison says that he relayed information about the contact and impressed upon them the fact the ICJP could “make a mess of it, that they could be settling for less than what they had the potential for achieving.”

GF: “They were then allowed by the British authorities to send Danny Morrison secretly into the prison for discussions with the hunger strikers and with the IRA leader there, Brendan McFarlane. This visit was later described by the IRA as a test of the authority of the British government representative in touch with them to bypass the NIO.”

DM: After exchanges, Mountain Climber’s offer (concessions in relation to aspects of the five demands) goes further than ICJP’s understanding of government position. Sinn Fein’s Danny Morrison secretly visits hunger strikers. Separately, he meets prison OC Brendan McFarlane, explains what Mountain Climber is offering should hunger strike be terminated. McFarlane meets hunger strikers.

DM: Morrison is allowed to phone out from the doctor’s surgery. Tells Adams that prisoners will not take anything on trust, and prisoners want offers confirmed and seek to improve them. While waiting for McFarlane to return Morrison is ordered out of the prison by a governor [John Pepper].

Padraig O’Malley, Biting at the Grave, pg 92: On Sunday, 5 July, Bishop O’Mahony, Hugh Logue and Father Crilly went back to the Maze/Long Kesh to talk with McFarlane. They spent about four hours with him.

Sources various: McFarlane returns to block; sends O’Rawe a run-down of the offer from the Mountain Climber. McFarlane, as told to Brian Rowan: “And I said to Richard (O’Rawe) this is amazing, this is a huge opportunity and I feel there’s a potential here (in the Mountain Climber process) to end this.” O’Rawe and McFarlane agreed there was enough there to accept the offer: “We spoke in Irish so the screws could not understand,” Mr O’Rawe told the Irish News.“I said, ‘Ta go leor ann’ – There’s enough there. He said, ‘Aontaim leat, scriobhfaidh me chun taoibh amiugh agus cuirfidh me fhois orthu’ – I agree with you, I will write to the outside and let them know.” Conversation confirmed by prisoners on the wing.

DM: ICJP visits hunger strikers and offers themselves as mediators. Hunger strikers say they want NIO rep to talk directly to them. Request by hunger strikers to meet McFarlane with ICJP is refused by NIO. Mountain Climber is told that prisoners want any offer verified.

Padraig O’Malley, Biting at the Grave, pg 93: “That evening the commissioners met with the prisoners again for about two and a half hours. This time the conversation centred on the question of guarantees – although the hunger strikers had not indicated that they regarded what was being proposed as being fully acceptable. They would, they said, have to consult their colleagues. […] They wanted a senior official from the NIO to come into the prison and spell out to them what was on offer – they would have to hear it from the British themselves rather than take the Commission’s word for it. Nevertheless the focus on the question of guarantees led the commissioners to believe that what had been put on offer the day before had not been repudiated, even after overnight consideration.”

““On the last night,” says Logue, “they [the hunger strikers] were all saying that we had to square any settlement we had, even if it was acceptable to them, with Bik.” In short, what the prisoners appeared to be saying was that if the terms were acceptable to McFarlane, they were acceptable to them. McFarlane was down the corridor in his bed – he had been brought into the hospital wing that evening and provided with a bed there so he could stay over and be available for consultation with the commissioners if the need arose. O’Mahony and Logue went down to talk to him. “He listened to us for about two minutes,” says Logue, “and turned around and went back to sleep and Joe McDonnell was going to be dead within thirty-six hours and I never forgave him for that. He was not in the business of trying to get a solution.” Nevertheless, the commissioners left in a hopeful state. Before they left, Kieran Doherty spoke briefly in Gaelic to Oliver Crilly. Doherty, Crilly told Logue, had told him that if somebody came in and read the terms out to the hunger strikers, they would accept them.”

Comm to Brownie from Bik (6.7.81 11pm – referring to events of the 5th):

“….Anyway Pennies will have filled you in on main pointers. The Bean Uasal has a time table of meetings, OK. At them all the same line was pushed by the Commission. You should have the main points from Pennies. They have maintained to myself and hunger strikers that principle of five demands is contained within the stuff they are pushing and that Brits won’t come with anything else.”

“I spent yy [yesterday] outlining our position and pushing our Saturday document as the basis for a solution. I said parts of their offer were vague and much more clarification and confirmation was needed to establish exactly what the Brits were on about. I told them the only concrete aspect seemed to be clothes and no way was this good enough to satisfy us. I saw all the hunger strikers yesterday and briefed them on the situation. They seemed strong enough and can hold the line alright. They did so last night when Commission met them. There was nothing extra on offer – they just pushed their line and themselves as guarantors over any settlement. The hunger strikers pushed to have me present, but NIO refused this and Commission wouldn’t lean hard enough on NIO. The lads also asked for NIO representative to talk directly to them, but the Commission say this is not on at all as NIO won’t wear. During the session H. Logue suggested drafting a statement on behalf of the hunger strikers asking for Brits to come in and talk direct, but lads knocked him back. A couple of them went out and made a phone call to NIO on getting me access to meeting and on getting NIO rep. They didn’t really try for me, according to Lorny, because when asked they said they didn’t want to push too hard and had been put off by the Brit’s firm refusal. Meeting terminated about midnight and Bishop O’Mahoney and J. Connolly paid me a short visit just to let me know the crack. Since then I haven’t been to see anyone except Lorny and Mick Devine on the way back to the block this morning. Requests to see hunger strikers and O/Cs have not been answered at all…I’m instructing Lorny to tell hunger strikers (if they are called together) not to talk to anyone till they get their hands on me. OK? By the way Joe was unable to attend last night’s session.”

Jack Holland & Henry McDonald, INLA, Deadly Divisions, page 179:

“Shortly before Joe McDonnell’s death, Councillor Flynn received a telephone call from a man in the Northern Ireland Office, who told him to go to Long Kesh. “There are developments,” was all he said. Even though it was late at night, Flynn went, accompanied by Seamus Ruddy. The NIO official, who refused to give his name, met him, and revealed that there had been discussions between Sinn Fein and the government and that it looked like they might settle. Flynn was given permission to go into the jail and speak to Lynch and Devine, who corroborated the NIO man’s assertion but said that the five demands were not being met, so whatever the Provisionals did, the INLA hunger strikers would not budge. Flynn could not get the official to reveal what was being offered. Later, when he confronted the Provisionals, they denied that they were engaged in any secret talks with the NIO.”

6 July

Brendan Duddy’s Mountain Climber notes:

The S.S. [Shop Stewards/Adams Committee] fully accept the posal — as stated by the Union MemBship [The Workers/Prison Leadership]

And that is the only Basis for a successful draft proposal by the Management. [British/Thatcher]

It is essential that a copy of the draft be in the S.S. hands Before it is made public.

To enable the S.S. to apr – up

or to point out any difficulty before publication

If it is pub. without prior sight and agreement the S.S. would have to disapprove it.

Monday Morning

July 6th.

Richard O’Rawe, Blanketmen, page 184:

“On the afternoon of 6 July, a comm came in from the Army Council saying that it did not think the Mountain Climber’s proposals provided the basis for a resolution and that more was needed. The message said that the right to free association was vital to an overall settlement and that its exclusion from the proposals, along with ambiguity on the issue of what constituted prison work, made the deal unacceptable. The Council was hopeful, though, that the Mountain Climber could be pushed into making further concessions. As usual, the comm had come from Gerry Adams, who had taken on the unenviable role of transmitting the Army Council’s views to the prison leadership.”

DM: Gerry Adams confides in ICJP about secret contact and the difference in the offers. Commission is stunned by disclosure. It confronts Alison and demands that a guarantor goes into the jail and confirm what is on offer. Alison checks with his superiors and states that a guarantor will go in at 9am the following morning, Tuesday, 7 July. Hunger strikers are told to expect an official from the NIO.

GF: “On Monday, 6 July at 3:30pm, according to the account given to me shortly after these events, Gerry Adams phoned the commission seeking a meeting, revealing that the British government had made contact with him. An hour and a half later two members of the commission met Adams and Morrison, who told them that this contact was ‘London based’ and had been in touch with them ‘last time round’, i.e. during the 1980 hunger strike. Adams demanded that the commission phone the NIO to cancel their meeting.”

GF: “Members of the commission, furious at this development, then met Allison and four of his officials. They asked him if he had been in communication with the hunger strikers or with those with authority over them. He said that no member of his office had been in contact, and, when pressed, repeated this line. They then discussed the Commission’s own proposals.”

GF: “When the commission contacted us immediately after this meeting, they told us nothing about the London contact with Adams and Morrison – understandably, given that this was a telephone call – which in any event still did not loom large in their eyes at that point beside the agreement they believed they had reached, which indeed seemed to them to have settled the dispute and to be about to end the hunger strike.”

GF: “The commission had produced to Allison the statement on which they had been working, which they described as ‘a true summary of the essential points of prison reform that had emerged.’ They told Allison that this statement was considered by the hunger strikers to be ‘the formation [sic] of a resolution of the hunger strike,’ provided that they received ‘satisfactory clarification of detail and confirmation by an NIO official to the prisoners personally of the commitment of the British Government to act according to the spirit and the letter’ of the statement.”

GF: “Although there was a difference of opinion on whether certain of the concessions were ‘illustrative’ or not, this does not seem to have been a problem for the British at the time, since Allison went out to make a phone call and then came back to say that he had approval. He proposed that an NIO official would see the prisoners with the governor by mid-morning the following day, Tuesday. When we received this information Demot Nally phoned the British Ambassador to urge that this confirmatory visit take place as soon as possible.”

GF: “Late that night, however, the commission was phoned by Danny Morrison seeking a meeting, which they refused; but half an hour later he arrived at the hotel, saying that the Sinn Fein-IRA contacts with the British were continuing through the night and that he needed to see the actual commission proposals. This request was refused, although he was given the general gist of them.”

Brendan Duddy’s Mountain Climber notes:

Reply 11:30 PM July 6

The British Gov. is preparing to issue a statement only if there is an immediate end to the hunger strike.

(A) Prison reg. in Armagh would become general in NI prison ie civian clothing

B Visits as for conforming prisons

C Re. as stated on June 30 by Sec of State

7 July

DM: Republican monitors await response from Mountain Climber.

DM: 11.40am: Bishop O’Mahoney [ICJP] telephones Alison asking where the guarantor is. Alison suggests he and the ICJP have another meeting. O’Mahoney tells him he is shocked, dismayed and amazed that the government should be continuing with its game of brinkmanship. He says: “I beg you to get someone into prison and get things started.”

DM: 12.18pm: ICJP decides to hold 1pm press conference outlining what had been agreed by the government and explain how the British had failed to honour it.

DM: 12.55pm: NIO phones ICJP and says that an official would meet the hunger strikers that afternoon.

DM: 1pm: ICJP calls off its press conference.

GF: “On Tuesday afternoon, Gerry Adams rang to say that the British had now made an offer but that it was not enough. Three members of the commission then met Adams and Morrison, who produced their version of the offer that they said had been made to them. The commission saw this as almost a replica of their own proposals but with an additional provision about access to Open University courses.”

Brendan Duddy’s Mountain Climber notes:

Freedom of Movement would be permitted within each wing. Prison officer would maintain the total control of supervision during these periods:

Prison work will vary between Cell and Block maintenance, educational, cultural subjects ie Open University, toy making for charities. Building projects, ie New Church.

FOI Document 1: “Extract from a letter dated 8 July 1981 from 10 Downing Street to the Northern Ireland Office”

“Your Secretary of State said that the message which the Prime Minister had approved the previous evening had been communicated to the PIRA. Their response indicated that they did not regard it as satisfactory and that they wanted a good deal more.”

“That appeared to mark the end of the development, and we had made this clear to the PIRA during the afternoon.”

DM: “Late afternoon: Statement from PRO, H-Blocks, Richard O’Rawe: “We are very depressed at the fact that our comrade, Joe McDonnell, is virtually on the brink of death, especially when the solution to the issue is there for the taking. The urgency of the situation dictates that the British act on our statement of July 4 now.””

FOI Document 1: “This had produced a very rapid reaction which suggested that it was not the content of the message which they had objected to but only its tone.”

GF: “Meanwhile the commission had spent an agonising day, for while London had been negotiating with the IRA, Allison and the NIO had prevaricated about the prison visit, repeatedly promising that the official was about to go to the prison.”

DM: 4pm: NIO tells ICJP that an official will be going in but that the document was still being drafted.

Padraig O’Malley: Biting at the Grave, pg 97: “At one point, David Wyatt, a senior NIO official who had sat in on most of the discussions, rang to explain the delay: a lot of redrafting was going on and it had to be cleared with London.”

DM: 5.55pm: ICJP phones Alison and expresses concern that no official has gone in.

DM: 7.15pm: ICJP phones Alison and again expresses concern.

FOI Document 1: “The question now for decision was whether we should respond on our side. He had concluded that we should communicate with the PIRA over night a draft statement enlarging upon the substance of the previous evening but in no way whatever departing from its substance. If the PIRA accepted the draft statement and ordered the hunger strikers to end their protest the statement would be issued immediately. If they did not, this statement would not be put out but instead an alternative statement reiterating the Government’s position as he had set it out in his statement of 30 June and responding to the discussions with the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace would be issued. If there was any leak about the process of communication with the PIRA, his office would deny it.”

GF: “At 8:30pm, however, Morrison and a companion had come without warning to the hotel where the commission had its base. Their attitude was threatening. Morrison said their contact had been put in jeopardy as a result of the commission revealing its existence at its meeting with Allison; the officials present with Allison had not known of the contact. Despite this onslaught the commission refused to keep Morrison informed of their actions.”

DM: 8.50pm: NIO tells ICJP that the official will be going in shortly.

DM: 10pm: Alison tells ICJP that no one would be going in that night but would at 7.30 the next morning and claims that the delay would be to the benefit of the prisoners. Republican monitors still waiting confirmation from Mountain Climber that an NIO representative will meet the hunger strikers. The call does not come.

GF: “At ten o’clock that night Allison phoned to say that the official would not now be going to the prison until the following morning – adding, however, that this delay would be to the prisoners’ benefit.”

Padraig O’Malley, Biting at the Grave, pg 97: “Asked by Logue why no representative had been sent into the prison that morning, Logue says that Alison replied, “Frankly, I was not a sufficient plenipotentiary.””

FOI Document 2: “Extract from a Telegram from the Northern Ireland Office to the Cabinet Office”

PLEASE PASS FOLLOWING TO MR WOODFIELD

MIPT contains the text of a statement which SOSNI proposes to authorise should be released to the hunger-strikers/prisoners and publicly. The statement contains, except on clothing, nothing of substance which has not been said publicly, and the point on clothing was made privately to the provos on 5 July. The purpose of the statement is simply to give precise clarification to formulae which already exist. It also takes count of advice given to us over the last 12 hours on the kind of language which (while not a variance with any of our previous public statements) might make the statement acceptable to the provos.

The statement has now been read and we await provo reactions (we would be willing to allow them a sight of the document just before it is given to the prisoners and released to the press). It has been made clear (as the draft itself states) that it is not a basis for negotiation.”

FOI Document 1: “The meeting then considered the revised draft statement which was to be communicated to the PIRA. A number of amendments were made, primarily with a view to removing any suggestion at all the Government was in a negotiation. A copy of the agreed version of the statement is attached.”

“The Prime Minister, summing up the discussion, said that the statement should now be communicated to the PIRA as your Secretary of State proposed. If it did not produce a response leading to the end of the hunger strike, Mr Atkins should issue at once a statement reaffirming the Government’s existing position as he had set out on 30 June.”

10pm Comm to Brownie from Bik:

“…I don’t know if you’ve thought on this line, but I have been thinking that if we don’t pull this off and Joe dies then the RA are going to come under some bad stick from all quarters. Everyone is crying the place down that a settlement is there and those Commission chappies are convinced that they have breached Brit principles. Anyway we’ll sit tight and see what comes…”

8 July

DM: 4.50am Joe McDonnell dies on the 61st day of his hunger strike.

GF: “Just before 5:00am that night Joe McDonnell died. At 6:30 the governor, in the presence of an NIO official, read a statement to the prisoners that differed markedly from the one prepared by the commission, and, in their view, approved by Allison thirty-six hours earlier. Fifteen minutes later Adams rang the commission to say that at 5:30am the contact with London had been terminated without explanation.”

Gerry Adams, Before the Dawn, page 299:

“Very early one morning I and another member of our committee were in mid-discussion with the British in a living room in a house in Andersonstown when, all of a sudden, they cut the conversation, which we thought was quite strange. Then, later, when we turned on the first news broadcast of the morning, we heard that Joe McDonnell was dead. Obviously they had cut the conversation when they got the word. They had misjudged the timing of their negotiations, and Joe had died much earlier than they had anticipated.”

DM: 9am: An NIO official visits each hunger striker in his cell and reads out a statement which says that nothing has changed since Humphrey Atkins’ policy statement of 29 June, thus suggesting that there was no new document being drafted as claimed by the NIO at 4pm on 7 July.

John Blelloch: “[…] the problem as always was seeing whether we could find some fresh statement of the government’s position which respected all our, which abided by our principal objectives which we adhered to throughout the hunger strike but nevertheless constituted some sort of opportunity for the prisoners to come off it. As far as I remember the delay on that was actually getting final agreement to the text of what might be said, which was not easy, and in the event McDonnell died before that process could be completed and of course thereafter it collapsed.” – 1986 interview with author Padraig O’Malley

GF: “When we heard the news of Joe McDonnell’s death and of the last-minute hardening of the British position, we were shattered. We had been quite unprepared for this volte-face, for we, of course, had known nothing whatever of the disastrous British approach to Adams and Morrison. Nor had we known of the IRA’s attempts – regardless of the threat this posed to the lives of the prisoners, and especially to that of Joe McDonnell – to raise the ante by seeking concessions beyond what the prisoners had said they could accept. We had believed that the IRA had been in effect bypassed by the commission’s direct contact with the prisoners at the weekend, which we had helped to arrange.”

DM: ICJP holds press conference and condemns British government and NIO for failing to honour undertaking and for “clawing back” concessions.

GF: “That afternoon the Commission for Justice and Peace issued a statement setting out the discussions they had had with Allison leading to the agreement reached on Monday evening. I then issued a statement recalling that I had repeatedly said that a solution could be reached through a flexibility of approach that need not sacrifice any principle. While the onus to show this flexibility rested with both sides, the greater responsibility must, as always, rest on those with the greater power.”

10 July

DM: ICJP leaves Belfast.

10pm comm to Brownie from Bik:

“…No one will be talking to them [ICJP] unless I am present and then it will only be to tell them to skit OK. More than likely you lot have already done a fair job on them this evening. Sincerely hope so anyway. If we can render them ineffective now, then we leave the way clear for a direct approach without all the ballsing about. The reason we didn’t skite them in the first instance was because I was afraid of coming across as inflexible or even intransigent. Our softly softly approach with them has left the impression that we were taking their proposals as a settlement. I’m sorry not I didn’t tell them to go and get stuffed.”

Comm to An Bean Uasal from Bik, Fri. 10.7.81

“Comrade, got your comm today alright. Find here a statement attacking ICJP as requested.”

12 July

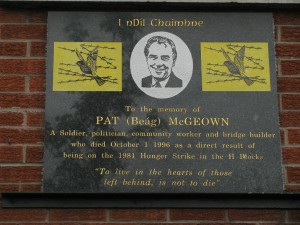

Comm to Brownie from Bik

“…Talking to Pat [McGeown] this morning and he reckons we should not have cut out the Commission. I explained the crack in full, but he’s one for covering all exits no matter what the score is. Just thought I’d mention that, OK?…”

—

GF: “I have given a full account of these events (some of them unknown to us at the time they took place) because in retrospect I think that the shock of learning that a solution seemed to have been sabotaged by yet another and, as it seemed to us, astonishingly ham-fisted approach on behalf of the British government to the IRA influenced the extent and intensity of the efforts I deployed in the weeks that followed, in the hope – vain, as it turned out – of bringing that government back to the point it had apparently reached on Monday 6 July.”

Sourced from:

Danny Morrison, Timeline: 2006 & 2009

Garret Fitzgerald, Excerpt from autobiography, All in a Life, 1991, pages 367-371

Brendan Duddy, Mountain Climber notes

Freedom of Information documents, Sunday Times website

Gerry Adams, Excerpt from autobiograpy, Before the Dawn, 1996, page 299

Padraig O’Malley, Biting at the Grave, 1990, page 90-98; interview with John Blelloch, 1986

Jack Holland & Henry McDonald, INLA, Deadly Divisions, 1994, page 179

Richard O’Rawe, Blanketmen, 2005, page 284

David Beresford, comms from Ten Men Dead

Brian Rowan, interview with Brendan “Bik” McFarlane, 4 June, 2009

Steven McCaffrey, Irish News, Former comrades’ war of words over hunger strike, 12 March 2005

Joe McDonnell’s grandson Caolan presents the Joe McDonnell Cup to Captain Gary Lennon of Sarsfields

Joe McDonnell’s grandson Caolan presents the Joe McDonnell Cup to Captain Gary Lennon of Sarsfields

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.