Aug 8, 2009

“Rusty Nail”: Gerry Adams speaking with Kieran Doherty, 29 July 1981

Saturday, August 08, 2009

Gerry Adams and Kieran Doherty, 29 July 1981

Rusty Nail at Slugger O’Toole

Writing on his blog, Gerry Adams relates an anecdote from his 29 July 1981 visit with Owen Carron to the hunger strikers in Long Kesh. This anecdote is sourced from his autobiography, Before the Dawn. It is important to put the account of this conversation into context, in order to fully appreciate its meaning. Firstly, Kieran Doherty’s condition was dire; he was nearly blind, had considerable difficulty hearing, and was demonstrably ‘delirious’, hallucinating and unaware of his surroundings. At this stage, when he was conversing with Adams, he was in no position to be making any strategic decisions. He was hardly fit to process any information about the negotiations with the British, had he been fully informed, being conducted on his behalf by Adams. As told by Adams, Kieran Doherty was blind and confused, despite being described as ‘firm’ on the five demands; he lost track of who was in the room with him, greeting Bik McFarlane only to ask not much later where Bik was, and to ask after the boys repeatedly, even after his questions had already been answered. Yet it seems today Adams is holding up this conversation as some sort of defense against the charge that the hunger strikers were sacrificed for Sinn Fein’s political gain.

What is really significant about this piece is that it shows the hunger strikers were unaware that they had already broken Thatcher. From at least early July and possibly before, if some accounts are to be believed, she was offering Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness four of the five demands and by the time Gerry Adams was sitting with Kieran Doherty, the offer from the British that Adams had been negotiating was what the prisoners got when the hunger strike ended in October.

Although already having won the concession of letters and parcels, only 10 days before the 29 July meeting with the hunger strikers Adams was still stalling the British, seeking clarification over what could be in the parcels. (“Association during leisure hours was not enough and in addition they would need specific assurances as to what they would be allowed to receive in parcels.” Beresford, Ten Men Dead, pg 325.) The hunger strikers’ commitment was used by Adams as leverage in the negotiations with the British, although by this point the hunger strikers, according to Pat McGeown, whom Bik McFarlane was striving mightily to keep in line and silenced, were more committed to each other and those who had preceded them in death than they were tied down to the details of the five demands. “When Gerry was in I didn’t say anything to him,” [McGeown] says. “Bik had already said to me, ‘Don’t make your opinions known,’ to which I had given my commitment. I just accepted [the situation].” (O’Malley, Biting at the Grave, pg 83.)

To Brownie from Bik Sun 26.7.81

“…had a long yarn with Pat Beag [McGeown] this morning and impressed upon him the necessity of keeping firmly on the line. I explained that independent thought was sound, but once it began to stray from our well considered and accepted line that it became extremely dangerous. He accepted what I said alright. Also I stressed the need for all of us to have confidence in you lot.” (Comm quoted in Beresford, Ten Men Dead, pg 333.)

By August, after having had the visit from Adams and Carron, McGeown and Devine were discussing coming off the strike; neither wanted to be seen as saving himself but both recognised the futility of carrying on – except for one strategic gain: the election of Owen Carron. “I [McGeown] said to him [Devine], ‘Hold out for ten days. After the Fermanagh-South Tyrone by-election, I don’t see any political point in us continuing the hunger strike and I’ll be saying that quite openly.’ To say to him [Devine] to come off it before it [the by-election], politically I did think we needed to stay until the whole process had been completed with Owen Carron.” (O’Malley, Biting at the Grave, pg 84.) Devine died the day of the election; he was the last hunger striker to die.

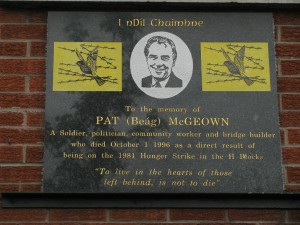

I nDíl Chuímhne

To the memory of PAT (Beág) McGeown

A Soldier, politican, community worker and bridge builder

who died October 1 1996 as a direct result of

being on the 1981 Hunger Strike in the H Blocks

“To live in the hearts of those left behind, is not to die”

– Plaque outside Sinn Fein headquarters on Falls Road

An Bean Uasal from Bik 28.7.81

“…Was up in hospital tonight. […] Doc was able to talk, but became delirious and told me he was ‘talking to Bik earlier on and had a yarn with Bobby’. He’s practically blind and has great difficulty in hearing. His spirit is strong and he is very determined.” (Comm quoted in Beresford, Ten Men Dead, pg 338.)

Gerry Adams, Leargas blog:

I thought of the last time I saw Kieran. In the prison hospital in the H Blocks of Long Kesh. By this time he was the TD for Cavan Monaghan. It was the 29 July 1981. Kieran died on August 2.

‘I’m not a criminal.’ He said

.

‘For too long our people have been broken. The Free Staters, the church, the SDLP. We won’t be broken. We’ll get our five demands. If I’m dead … well, the others will have them. I don’t want to die, but that’s up to the Brits. They think they can break us. Well they can’t.’ He grinned self-consciously: Tiocfaidh ar lá.’

We shook hands before I left, an old internee’s hand-shake, firm and strong.

‘Thanks for coming in, I’m glad we had that wee yarn. Tell everyone, all the lads, I was asking for them and … ‘ He continued to grip my hand.

‘Don’t worry, we’ll get our five demands. We’ll break Thatcher. Lean ar aghaidh.

Talking later to Kieran’s father Alfie, his eyes brimming with unshed tears, in the quiet cells in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh, I felt a raw hatred for the injustice which created this crisis.

I am glad to say that I still feel the same today 28 years after Kieran’s death.

Gerry Adams, Before the Dawn, pages 308-310:

“Brendan [McFarlane] arranged for us to go and see Kieran Doherty. I told the lads that I wouldn’t tell Doc of their position.

‘He knows it anyway,’ someone said.

‘We saw him last night after Father Crilly’s visit.’

‘I know,’ said I.

Doc was propped up on one elbow; his eyes, unseeing, scanned the cell as he heard us entering.

‘Mise atá ann,’ (‘It’s me’) said Brendan McFarlane.

‘Ahh Bik, cad é mar atá tú?’ arsa Doc. (‘Ahh Bik, how are you?’ Doc said.)

‘Nílim romh dhona, agus tú féin?‘ (‘I’m not too bad, and yourself?’)

‘Tá mé go hiontach; tá daoine eile anseo? Cé…?‘ (‘I’m great; are there other people here? Who…?’)

‘Tá Gerry Adams, Owen Carron agus Seamus Ruddy anseo. Teastaíonn uatha caint leat.‘ (‘Gerry Adams, Owen Carron, and Seamus Ruddy are here. They want to speak with you.’)

‘Gerry A’, fáilte.‘ (‘Gerry A’, welcome.’) He greeted us all, his eyes following our voices. We crowded around the bed, the cell much too small for four visitors. I sat on the side of the bed. Doc, whom I hadn’t seen in years, looked massive in his gauntness, as his eyes, fierce in their quiet defiance, scanned my face.

I spoke to him quietly and slowly, somewhat awed by the man’s dignity and by the enormity of our mission.

He responded to my probing with paitence.

‘You know the score yourself,’ he said, ‘I’ve a week in me yet. How is Kevin [Lynch] holding out?’

‘You’ll both be dead soon. I can go out now, Doc and announce that it’s over.’

He paused momentarily and reflected, then: ‘We haven’t got our five demands and that’s the only way I’m coming off. Too much suffered for too long, too many good men dead. Thatcher can’t break us. Lean ar aghaidh. I’m not a criminal.’

I continued with my probing. Doc responded.

‘For too long our people have been broken. The Free Staters, the church, the SDLP. We won’t be broken. We’ll get our five demands. If I’m dead…well, the others will have them. I don’t want to die, but that’s up to the Brits. They think they can break us. Well they can’t.’ He grinned self-consciously. ‘Tiocfaidh ár lá.‘ (‘Our day will come.’)

‘How are you all keeping? I’m glad you came in. I can only see blurred shapes. I’m glad to be with friends. Cá bhfuil Bik? (Where is Bik?) Bik, stay staunch. How’s the boys doing?’

We talked quietly for a few minutes. Owen got another ribbing about the election. We got up to go. I told Doc to get the screw to give us a shout if he wanted anything.

We shook hands, an old internee’s handshake, firm and strong.

‘Thanks for coming in, I’m glad we had that wee yarn. Tell everyone, all the lads, I was asking for them and…’ He continued to grip my hand.

‘Don’t worry, we’ll get our five demands. We’ll break Thatcher. Lean ar aghaidh.’

Outside Doc’s cell, the screw led us in to speak to Kieran’s father, Alfie, and brother, Michael, who had just arrived to relieve Kieran’s mother.

We spoke for about five minutes. I felt an immense solidarity with the Doherty family, broken-hearted, like all the families, as they watched Kieran die. Yet because they understood their son, they were prepared to accept his wishes and were completely committed to the five demands for which he was fasting.

Talking to Alfie, his eyes brimming with unshed tears, in the quiet cells in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh, I felt a raw hatred for the injustice that created this crisis. Alfie, concerned for us, had a quiet word with Bik McFarlane and left to sit with Kieran.”

Note: Kieran Doherty died 4 days later.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

[…] Note: See also Before the Dawn, pages 308-310. […]