Apr 28, 2013 Comments Off on UPDATED: National Archives 30 Year Papers – July, 1981

UPDATED: National Archives 30 Year Papers – July, 1981

Note: This was originally published on Slugger O’Toole in 2011, when many of the documents now released individually via the Thatcher Foundation in 2013, were first released by the National Archives as part of the 30 year papers for 1981. New, additional comments have been added at the end of the post and are noted with an asterik***

[scribd id=138328261 key=key-2nfz63hlw9ex4oft0lug mode=scroll]

National Archives 30 Year Papers – July, 1981

Rusty Nail

Slugger O’Toole

Fri 30 December 2011

The 30 year papers for 1981 are being released, and they include many documents covering the hunger strike. Here are some quick notes about file PREM/19/506, which covers the period of the early July offer.

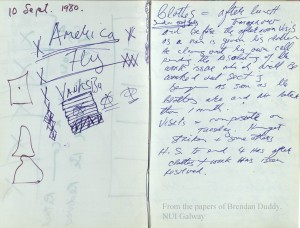

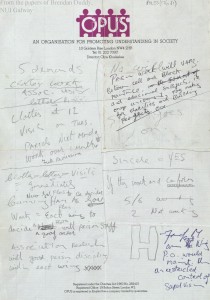

Specifically, this is a quick sketch of pages 13-26 of the PDF, a telegram that comprehensively details the conversations the Mountain Climber/Brendan Duddy (referred to as “SOON”) had with the British Government, in which he was relaying messages from the Provisional IRA. This is the British Government’s notes of their negotiations with the Adams Committee.

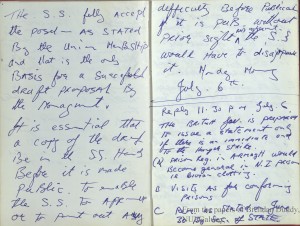

The first thing it confirms is that Duddy’s notes were extremely accurate. The telegram detailing “Call No 8 – 0100-0117 6 July” reflects his recently released papers, where in paragraph 41 he relayed that “The Provisionals fully accept the position as stated by the Prisoners” – this sentence was underlined by a reader of the telegram for emphasis.

In Call No 7, 2300-2400, 5 July, paragraph 35, he describes the Provisionals as being extremely unhappy with what they called the “bully boy” tactics of the ICJP: “From an apparently enthusiastic position, SOON (Duddy) had been called into an angry and hostile meeting of the Provisionals almost verging on a complete breakdown. The Provisionals view of the situation is that the prisoners’ statement had been totally ignored by the ICJP”. The call goes onto describe what really seems as an attempt to muddy waters over the ICJP’s participation – in effect, to get the British to pressure the ICJP to back off – though it was delivered in a confused and ham-fisted way. It would also seem that the fact the hunger strikers were listening to the ICJP and that the prisoners had accepted the offer was rattling those doing the negotiating.

Another interesting thing is that the Provos wanted Adams and/or McGuinness to go in with Morrison to see the hunger strikers. When it was made clear that Adams and McGuinness were unacceptable, Ted Howell was then proposed. (paragraph 33, Call No 6, 1750-1817, 5 July)

The most interesting thing about this is the confirmation that the full Army Council was completely in the dark about the Mountain Climber negotiations and offer.

The first call, 2200-2312, 4 July, sets the scene in that regard:

Paragraph 4:

“…the timing of the release of the [prisoners’] statement had caught the Provisionals unaware. The senior members, and SOON claimed there were eight, were widely dispersed. Only Adams and O’Brady were readily available. They were regrouping and SOON’s Provisional contact had instructed him to stand by.”

Paragraph 6: “… secondly he stated that a meeting of the senior Provisionals had taken place on 28 June at which they considered realistic conditions for the ending of the hunger strike had been discussed.” (This was before the contact with the Mountain Climber/SOON was revived)

In Call No 2, 0230-0500, 5 July, paragraph 10: “SOON began by restating the Provisionals’ disorganised position. He pointed out that to take a decision of this magnitude required the presence of all 8 members. They would be unwilling to take any decision without a full complement.”

Was that a genuine position or a delaying tactic?

It is later that morning, during Call No 3, 1045-1125, 5 July, the fact that the full Army Council were unaware of what was being done is made clear:

Paragraph 15:

“He then returned to the subject of the prison visit. He said that the number of senior Provisionals with a full grasp of the situation including knowledge of the SOON channel and the status to enable them to act authoritatively was very limited. He said that if the key to accepting any agreement was persuation [sic], education and knowledge, then that is not available outside the very upper echelons of the Provisional Movement. It is not even available as of right to the entire PSF leadership. He said this poses a problem. In response to our request for suggestions of Provisionals who would fit this description, SOON produced Morrison, Adams and McGuinness as the only three candidates.”

Paragraph 16:

“SOON (Duddy) then proceeded to offer the Provisionals’ view of the ICJP. He said that determination still existed not to let the ICJP act as mediator. As a consequence, there was a body of opinion within the Provisional leadership, which was unaware of the SOON channel and, therefore, took a destructive view towards any current proposals since they believed they would involve the ICJP.”

One other aspect of this important document is amazing. It describes the ending of the first hunger strike:

Call No 2, 0230-0550 5 July, Paragraph 13:

“He said that one of the major difficulties over the implementation of the agreement at the end of the last hunger strike had been the attitude of some of the prison officers. He said that the Provisionals believed that HMG had been sincere in trying to implement their side of the agreement. The breakdown had occurred because some of the prisoners had been harassed by some of the prison officers. He, therefore, requested that in HMG’s proposals should be included an instruction to the Governor of the prison to encourage flexibility in the implementation of any agreement.” (emphasis mine)

Owen Bowcott, writing in today’s Guardian, has Danny Morrison’s reaction to the papers:

[Morrison] told the Guardian the documents vindicated the IRA’s decisions at the time. “I find these documents very refreshing,” he said. “At least they have published what was happening. These conversations were recorded by Michael Oatley [the MI6 officer] or his secretary. We never got the final [British] position [before hunger striker] Joe O’Donnell died.” [***SEE BELOW FOR FURTHER COMMENT, ADDED 2013]

Recall ‘it was not the content of the message which they had objected to but only its tone’:

“[…] As far as I remember the delay on that was actually getting final agreement to the text of what might be said, which was not easy, and in the event McDonnell died before that process could be completed and of course thereafter it collapsed.” – 1986 John Blelloch interview with author Padraig O’Malley

As Gerry Adams described in Before the Dawn, page 299:

“Very early one morning I and another member of our committee were in mid-discussion with the British in a living room in a house in Andersonstown when, all of a sudden, they cut the conversation, which we thought was quite strange. Then, later, when we turned on the first news broadcast of the morning, we heard that Joe McDonnell was dead. Obviously they had cut the conversation when they got the word. They had misjudged the timing of their negotiations, and Joe had died much earlier than they had anticipated.”

*** FURTHER COMMENT ADDED, SPRING 2013:

The release via the Thatcher Foundation of itemised archival documents contains material that starkly contradicts Morrison’s 2011 claim that “We never got the final [British] position [before hunger striker] Joe O’Donnell died.”

In 2009, journalist Liam Clarke gained access to documents via a Freedom of Information request. Part of what was released to Clarke was an “EXTRACT FROM A LETTER DATED 8 JULY 1981 FROM 10 DOWNING STREET TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND OFFICE”, which also included an EXTRACT FROM A TELEGRAM sent from the NIO to the Cabinet. The significance of these extracts are fully understood with the release of the full documents, which now only has names redacted.

DOWNLOAD PDF: STATEMENT IMPORTANT

Comparing the 2009 release with the 2011 document, it is obvious this paragraph had been previously redacted:

NAME REDACTED said it was thought that the revised statement based upon the previous night’s message would be enough to get the PIRA to instruct the prisoners to call off the hunger strike. He then outlined the procedures that would be followed, if the PIRA said that they would call off the hunger strike. [emphasis added]

One can only speculate why that paragraph was censored in the 2009 FOI release. Was it too damning?

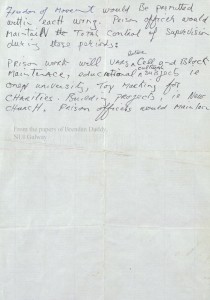

The statement referred to is included in this document and was released in 2009. It gives clothes; letters, parcels, and visits; restoration of remission; work and education, and allows for room on association and segregation. In other words, the hunger strikers had won their demands.

We know from the 2009 release of the extract of this telegram that, contrary to what Danny Morrison told Owen Bowcott in 2011, Adams did know “the final [British] position [before hunger striker] Joe O’Donnell died.”

The statement has now been read and we await provo reactions (we would be willing to allow them a sight of the document just before it is given to the prisoners and released to the press).

Why did Adams say no?

Abbreviated Timeline:

5th July

- Morrison goes into prison, tells McFarlane of offer from Thatcher, which McFarlane and O’Rawe agree is enough to accept

- Morrison does not tell hunger strikers details of the offer; he only tells them that they were in talks with the British and that the ICJP could mess things up (warns the hunger strikers off accepting anything the ICJP offers)

6 July

- (afternoon) Adams comm tells McFarlane and O’Rawe that “more was needed” – offer rejected.

- (late evening) Morrison tells ICJP that the Adams group contacts with the British were continuing through the night.

- 11:30pm – “The British Gov. is preparing to issue a statement only if there is an immediate end to the hunger strike.

(A) Prison reg. in Armagh would become general in NI prison ie civian clothing

B Visits as for conforming prisons ” – Brendan Duddy notes

7 July

- “On Tuesday afternoon, Gerry Adams rang [the ICJP] to say that the British had now made an offer but that it was not enough.” – Garret Fitzgerald

- “Your Secretary of State said that the message which the Prime Minister had approved the previous evening had been communicated to the PIRA. Their response indicated that they did not regard it as satisfactory and that they wanted a good deal more. That appeared to mark the end of the development, and we had made this clear to the PIRA during the afternoon. This had produced a very rapid reaction which suggested that it was not the content of the message which they had objected to but only its tone.”

- “4pm: NIO tells ICJP that an official will be going in but that the document was still being drafted.” – Danny Morrison

- “At one point, David Wyatt, a senior NIO official who had sat in on most of the discussions, rang to explain the delay: a lot of redrafting was going on and it had to be cleared with London.” – Padraig O’Malley: Biting at the Grave, pg 97

- British send draft statement to Adams group enlarging on previous offer; if accepted by Adams, statement issued immediately

- British believed this revised statement “would be enough to get the PIRA to instruct the prisoners to call off the hunger strike”

-

10pm

“…I don’t know if you’ve thought on this line, but I have been thinking that if we don’t pull this off and Joe dies then the RA are going to come under some bad stick from all quarters. Everyone is crying the place down that a settlement is there and those Commission chappies are convinced that they have breached Brit principles. Anyway we’ll sit tight and see what comes…” – Comm to Brownie (Adams) from Bik (McFarlane)

- Confirmation via telegram from NIO that the statement had been read to Adams group, and that they were awaiting the reply

8 July

- “Very early one morning I and another member of our committee were in mid-discussion with the British in a living room in a house in Andersonstown when, all of a sudden, they cut the conversation, which we thought was quite strange. Then, later, when we turned on the first news broadcast of the morning, we heard that Joe McDonnell was dead.” – Gerry Adams, Before the Dawn, page 299

See also: Prolonging the Hunger Strike: The Derailing of the ICJP

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.