May 20, 2013 Comments Off on 55 HOURS PART FOUR: WEDNESDAY 8 JULY 1981

55 HOURS PART FOUR: WEDNESDAY 8 JULY 1981

55 Hours: A day-by-day account of the events of early July, 1981.

Using the timeline created with documents from ‘Mountain Climber’ Brendan Duddy’s diary of ‘channel’ communications, official papers from the Thatcher Foundation Archive, excerpts from former Taoiseach Garrett Fitzgerald’s autobiography, David Beresford’s Ten Men Dead, Padraig O’Malley’s book Biting at the Grave, and INLA: Deadly Divisions by Jack Holland and Henry McDonald, Danny Morrison’s published timelines, as well as first person accounts and the books of Richard O’Rawe and Gerry Adams, the fifty-five hours of secret negotiations between British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Gerry Adams’ emerging IRA leadership group are examined day by day.

“I accept in a situation like that there has to be secret talks, has to be secrecy of some sorts, but when you are talking about men’s lives that are just dwindling away, they were entitled to the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.” – Brendan Hughes

PART FOUR: WEDNESDAY 8 JULY 1981

Early Morning

Death’s Brother, Sleep

Gerry Adams decided he needed some rest. He explains in Before the Dawn that he ‘started cat-napping during the day in order to be relatively fresh for negotiations at night’. Ten Men Dead details that Adams ‘had taken a break Tuesday evening’ and did not return to the safe house where the channel communications were conducted until ‘the early hours of the morning’.

A Time for Many Words and A Time for Sleep

According to Danny Morrison, at this point “Republican monitors [were] still waiting confirmation from Mountain Climber,” and he claims that “[t]he call does not come.” This is repeated in Ten Men Dead, where a member of the Adams Group in the safe house tells Adams upon his return from his cat-nap that nothing has come through. The impression is that the channel line had gone dead and the British were done with the communications.

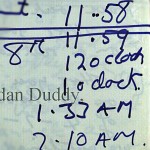

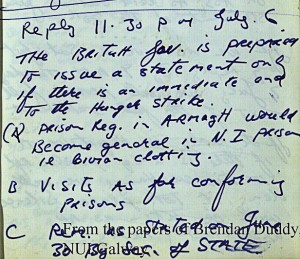

Brendan Duddy’s notes, however, offer a radically different perspective. In his diary, he has a series of times listed:

- 11:58

- 11:59

- 12:00 midnight

- 1:00 am

- 1:33 am

- 2:10 am

These times are then followed in the diary by the details of the offer made by Thatcher that could have ended the hunger strike.

It is unlikely that those times are a record of attempts made by the Adams Group to contact Thatcher, given they were waiting for her response to their 8pm messages, and Adams was not available.

Could it be that the list is an accounting of the amount of times Duddy had attempted to contact the Adams Group with Thatcher’s offer before Adams returned from his nap?

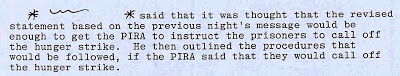

The calls from the Mountain Climber did come, it seems, numerous times, while Joe McDonnell was breathing his last four hours. Adams was not there to receive them until after 2 in the morning.When he had finally been contacted, the British were still hopeful. The NIO telegraphed Thatcher:

The statement has now been read and we await provo reactions (we would be willing to allow them a sight of the document just before it is given to the prisoners and released to the press). It has been made clear (as the draft itself states) that it is not a basis for negotiation.

The choreography was in place. Everything the Adams Group had asked for was there, such as the rephrasing on Work and Association. They were even given their added demand of the veto of sight before the prisoners were to be given the agreed statement and it was released publicly.

All that was needed was for the Adams Group to say it was enough to end the strike, and the process of saving the men’s lives would begin.

[British] The management will ensure that as substantial part of the work will consist of domestic tasks inside and outside the wings necessary for servicing the prisoners, such as cleaning and in the laundry and kitchen, construction work for example on building projects or making toys for charitable bodies and studying for Open University or other courses. The factory authority will be responsible for supervision.

The aim of the authority will be that prisoners should do the kind of work for which they are suited. But this will not always be possible and the authorities will retain responsibility for decisions.

“Little advance is possible on Association”

It (Association) will be permitted within each wing under supervision of factory staff.

(English language you can’t do any more than give freedom in a wing)

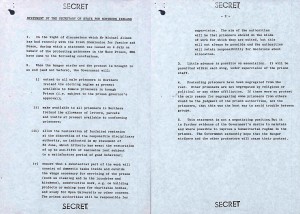

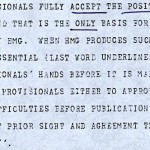

- In the light of discussions which Mr Michael Alison has had recently with the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace, during which a statement was issued on 4 July on behalf of the protesting prisoners in the Maze Prison, HMG have come to the following conclusions.

- When the hunger strike and the protest is brought to an end (and not before), the Government will:

- extend to all male prisoners in Northern Ireland the clothing regime at present available to female prisoners in Armagh Prison (i.e. subject to the prison governor’s approval);

- make available to all prisoners in Northern Ireland the allowance of letters, parcels and visits at present available to conforming prisoners;

- allow the restoration of forfeited remission at the discretion of the responsible disciplinary authority, as indicated in my statement of 30 June, which hitherto has meant the restoration of up to one-fifth of remission lost subject to a satisfactory period of good behaviour;

- ensure that a substantial part of the work will consist of domestic tasks inside and outside the wings necessary for servicing of the prison (such as cleaning and in the laundries and kitchens), constructive work, e.g. on building projects or making toys for charitable bodies, and study for Open University or other courses. The prison authorities will be responsible for supervision. The aim of the authorities will be that prisoners should do the kinds of work for which they are suited, but this will not always be possible and the authorities will retain responsibility for decisions about allocation.

- Little advance is possible on association. It will be permitted within each wing, under supervision of the prison staff.

- Protesting prisoners have been segregated from the rest. Other prisoners are not segregated by religious or any other affiliation. If there were no protest the only reason for segregating some prisoners from others would be the judgment of the prison authorities, not the prisoners, that this was the best way to avoid trouble between groups.

- This statement is not a negotiating position. But it is further evidence of the Government’s desire to maintain and where possible to improve a humanitarian regime in the prisons. The Government earnestly hopes that the hunger strikers and the other protesters will cease their protest.

It would be two hours until the Adams Group came back with any answer, and it was not the one anyone had hoped for.

Bad Faith

At 4am in the morning, the Adams Group send their first response to Thatcher’s latest offer through the channel. A request is made for Adams to go into the prison.

The purpose is listed as ‘1. To ensure success 2. To achieve’ — the notation in the diary is brief and vague, but asking for Adams to go in at that point — knowing the British had repeatedly rejected him when he was previously suggested was a bold request. Was it really necessary for Adams personally to go in for the strike to end? Would that be something worth rejecting the offer over?

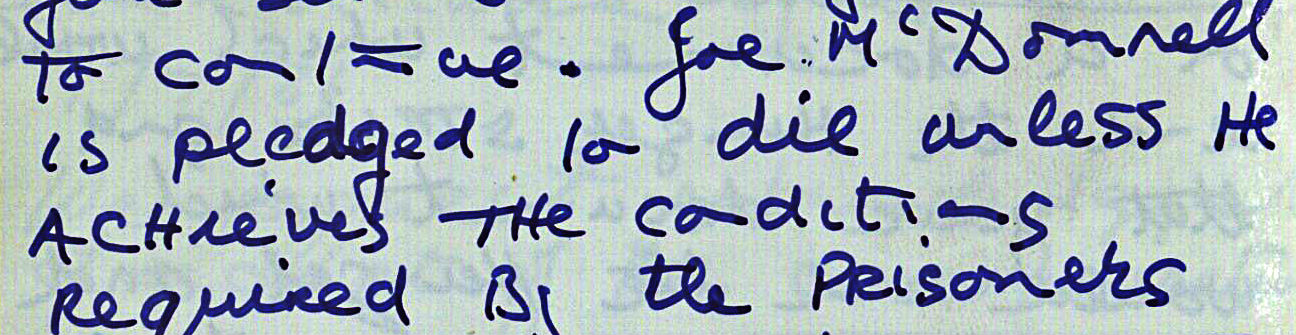

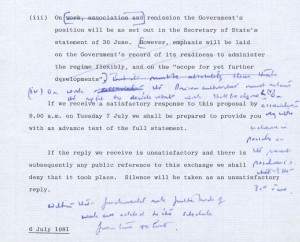

At 5am, the Adams Group sends a further new demand through the channel. In addition to the public document that Thatcher has drafted, they now want a private document to be drawn up as well. This private document, they demand, should be a ‘detailed nitty-gritty’ of work, association, and the rest of the prisoners’ demands.

They had already agreed that these details would be worked out after the hunger strike was called off. Now, at the exact moment while in the prison hospital Joe McDonnell’s sister Maura was shaking his still-warm body crying for him to not be dead, the Adams Group demanded even more upfront before they would consider ordering an end to the strike.

The Ante Raised

The British response to the new demands was not long in coming. The communication on the channel was over.

Adams imbues an air of mystery to the termination of the channel communication in Before the Dawn:

“Very early one morning I and another member of our committee were in mid-discussion with the British in a living room in a house in Andersonstown when, all of a sudden, they cut the conversation, which we thought was quite strange.”

Perhaps it was not so strange. Duddy’s diary contains the British reaction to the new demand — and the explanation for why the contact ended when it did. The response, which according to Adams came at 5:30am, is terse:

The management cannot contemplate the proposal for two documents set out in your last communication and now therefore the exchange on this channel to be ended.

At the last minute, acting in bad faith, the Adams Group demanded too much.

The Death of Joe McDonnell

Danny Morrison gives the time of Joe McDonnell’s death as 4:50am; that is when Father Murphy woke up Joe’s family, who were sleeping in the prison hospital, to tell them he had died, and his sister Maura, shouting and shaking him, desperately tried to bring him back.

Word confirming his death was slow in getting out, and somewhat confused. Duddy’s diary puts Joe’s death 17 minutes later, at 5:07, though it was not known he had died until the morning news broadcast; the Bobby Sands Trust as well as various other websites including the Sinn Fein bookshop, list his death at 5:11am; Padraig O’Malley writes that Joe died at 5:40am.

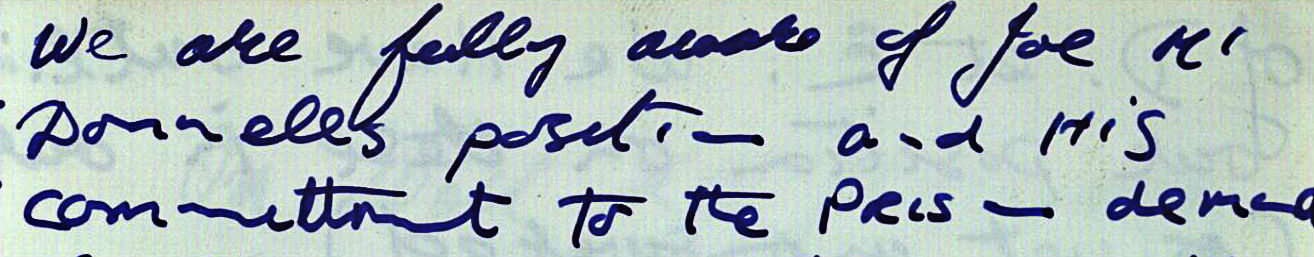

The Adams Group and the British, unaware he had died, were in discussions until 5:30am, and did not hear of his death immediately; it was a number of hours before they knew: “We first heard it on the 7:00am news,” Duddy records.

Adams’ autobiography confirms they did not know Joe had died while they were conducting the channel discussions: “Then, later, when we turned on the first news broadcast of the morning, we heard that Joe McDonnell was dead.”

Without divulging that at the time Joe was dying he was inserting another new demand into the process of settlement, Adams lets his readers believe the reason the British had ended their communication was because they had been informed of Joe’s death. But the times noted in Duddy’s diary, combined with the Adams Group’s new demand and the British reaction, make this impossible.

It was not Joe’s death that caused the British to end the channel discussion; it was the new, bad faith demand for more detailed documentation; details that the British believed had already been agreed could be worked out once the men had come off their strike, in order to save their lives.

By 6:30am the NIO finally sent in an official to read a statement of the British position to the prisoners.

As promised, given the rejection by the Adams Group of Thatcher’s offer, the statement was absent of any indication of the strides made in either the ICJP or Adams Group discussions.

According to Garrett Fitzgerald, Adams contacted the ICJP fifteen minutes after the NIO went into the prison, and immediately blamed the British. He ‘rang the commission to say that at 5:30am the contact with London had been terminated without explanation’.

Garrett Fitzgerald:

When we heard the news of Joe McDonnell’s death and of the last-minute hardening of the British position, we were shattered. We had been quite unprepared for this volte-face, for we, of course, had known nothing whatever of the disastrous British approach to Adams and Morrison. Nor had we known of the IRA’s attempts – regardless of the threat this posed to the lives of the prisoners, and especially to that of Joe McDonnell – to raise the ante by seeking concessions beyond what the prisoners had said they could accept.

The Fatal Wings of Time

“Don’t you worry about Joe McDonnell,” he said to Bik McFarlane in the canteen after Danny Morrison’s Sunday visit.

It was the first time Bik and Joe had ever met each other. Joe was ‘confined to a wheelchair’, his ‘head crouched low to one side’, and he ‘could barely hear’ what was said. He was in ‘an appalling condition’.

Yet he shook Bik’s hand despite immense pain.

“I might only last a few days but I’ll hang on as long as I can and buy all the time we need.”

Previously: Tuesday 7 July 1981

![Send on 5 of July Clothes = after lunch Tomorrow and before the the afternoon visit as a man is given his clothes He clears out his own cell pending the resolution of the work issue which will be worked out [garbled] as soon as the clothes are and no later than 1 month. Visits = [garbled] on Tuesday. Hunger strikers + some others H.S. to end 4 hrs after clothes + work has been resolved.](http://www.longkesh.info/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Pol35_0166_0001-150x150.jpg)

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.