May 16, 2013

55 HOURS PART THREE: TUESDAY 7 JULY 1981

55 Hours: A day-by-day account of the events of early July, 1981.

Using the timeline created with documents from ‘Mountain Climber’ Brendan Duddy’s diary of ‘channel’ communications, official papers from the Thatcher Foundation Archive, excerpts from former Taoiseach Garrett Fitzgerald’s autobiography, David Beresford’s Ten Men Dead, Padraig O’Malley’s book Biting at the Grave, and INLA: Deadly Divisions by Jack Holland and Henry McDonald, Danny Morrison’s published timelines, as well as first person accounts and the books of Richard O’Rawe and Gerry Adams, the fifty-five hours of secret negotiations between British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Gerry Adams’ emerging IRA leadership group are examined day by day.

PART THREE: TUESDAY 7 JULY 1981

Early Morning

Spanner in the Works

The Adams Group spent a considerable amount of the time the previous two days attempting to derail the ICJP effort. They had thrown a wobbler over the ICJP to the British, instructed the prisoners to freeze the ICJP out, and told the ICJP in no uncertain terms to back off after letting them know that they were in their own, more senior, talks with the British themselves.

The effect of telling the ICJP about their own secret talks was a spanner in the works, meant to slow things down. Certainly the ICJP reaction to the news meant their afternoon and evening were taken up with stunned confrontations and clarifications – valuable time wasted.

What More Was Needed

After getting the ‘general gist’ of the proposals the ICJP were given, the Adams Group prepared their response to Thatcher’s 11:30pm statement. Their reply, sent at 3:30am, backtracked on what they had previously indicated, and echoed the comm sent in to the prisoners Monday afternoon.

Previously, their position had been that ‘demands dealing with work and association could be subject to a series of discussions after the ending of the hunger strike’.

Now, however, the Adams Group were demanding that work and association must be dealt with immediately before they would make any decision on whether to accept the offer or not:

To assist us in taking a ?(firm)? decision on your proposals, elaboration on Point C – Remission, Point D – Work, Point E – Association is necessary. These are obviously the major points of contention which need to be resolved if the prison protests are to be permanently ended. The position outlined by you is not sufficient to achieve this.

On Work, the Adams Group wanted emphasis on ‘Self education’. For Association, “We believe there should be wing visits”. Full remission continued to be pushed for.

They wanted fuller detail put into the statement before agreeing to agree: “We and the prisoners need an outline of the specific improvements envisaged by you. We also require your attitude to the detailed proposals outlined by the prisoners”.

NIO Stalled

Asking at 3:30 in the morning for more detail, and pressing for clarification to happen before the sequence they had already agreed to, meant it would be impossible for anyone from the NIO to come in to speak with the prisoners at 9am, as the ICJP had thought they arranged.

By 11:40am, the ICJP, unaware that their agreement with the NIO was being thrown off course by the secret Adams-Thatcher talks, begged Alison to send the official in to the prisoners as promised. Alison, constrained by the channel discussions, could only stall for time, and promised the official would go in later in the afternoon.

Afternoon

The NIO was unable to conclude anything with the ICJP as the secret talks between Thatcher and the Adams Group were ongoing.

Gerry Adams and Danny Morrison also met again with members of the ICJP, according to Garrett Fitzgerald.

“On Tuesday afternoon, Gerry Adams rang to say that the British had now made an offer but that it was not enough. Three members of the commission then met Adams and Morrison, who produced their version of the offer that they said had been made to them. The commission saw this as almost a replica of their own proposals but with an additional provision about access to Open University courses.”

Were the Adams Group working towards achieving more than the ICJP, or were they working on delaying any settlement? Either way, as David Beresford in Ten Men Dead put it, “they desperately needed to get the commission out of the way”.

When to Hold and When to Fold

Humphrey Atkins continued to argue his position of standing firm with Thatcher, although like his earlier advice, Thatcher did not take it. Given what is evident in the record of channel communication, she believed if a settlement were to be achieved, and the hunger strike brought to an end, the opportunity lay with the Adams Group talks; standing firm in private with them would achieve nothing. As Adams described her in his autobiography Before the Dawn, “she was no stranger to expediency”.

She was no fool, either. In a letter containing a proposed draft statement which echoed his 30 June stance, Atkins observed the early morning rejection of the Adams Group: “Following the sending of the message which you approved last night, we have received, as you will know, an unsatisfactory response. That particular channel of activity is therefore now no longer active.”

Thatcher’s response to the Adams Group’s rejection simultaneously gave the Adams Group what they wanted – the demise of the ICJP initative – while at the same time appeared to close the channel.

Receiving a Rocket

The Mountain Climber channel with the Adams Group was temporarily closed in response to the 3:30am reply demanding more. Beresford writes that the British were

“’deeply disturbed’ by the abuse of confidence by which Alison had become involved. The message said that the line of contact was unknown to ‘the most senior of their people’ and if the confidentiality was abused the secret initiative must be put at risk.”

Adams and Morrison’s revelations to the ICJP had indeed been a spanner thrown into the works on a number of levels. Not only that, their response to the British offer was seen as a rejection and the British were appalled.

Mag cannot move

1. From the 30th June principle

2. Position of June went to the limits that we could do in our P?????

3. By suggesting that we do more, the SS [Adams Group] are inviting us to abandon our principles.

This we cannot do.

Their response amounts to a rejection.

We are appalled by this decision.

Our discussions with CJ have come to an end and they will have no further parts in our efforts to resolve the problem.

We are sorry if the problem has been ex. hopes raised false because of any false impression given by C. Jenkins Union

We are also deeply disturbed as we were told in June by the SS abuse of knowledge of the channel. C Jenkins as pre(vious??)=Krugs??? Has clearly been told of its existence and involved to activate it.

C Jenkins Union put it ?the? Mr A last night that this was a possibility open to many in a room full of people.

This must be in question, the future of the channels.

In keeping with the workplace code, where the Adams Group were the Shop Stewards, the prisoners the Union Membership and so on, the ICJP was aptly named as a competitor to Adams Group’s Shop Stewards, seeking to represent the prisoners. Their code name was the ‘C Jenkins Union’.

The British did not appreciate that the ICJP had been told of the existence of the secret talks and were less than pleased that the ICJP had then confronted Alison about them ‘in a room full of people’. The ICJP initiative was now dead in the water.

An Apology and the Ending of the ICJP

While the British were appalled by the rejection of their offer, the Adams Group does appear to have achieved their primary objective of sidelining the ICJP, and, remarkably, received an apology from the British. Both Adams and Morrison’s tantrums over the involvement of the ICJP and the breach of the confidentiality of their talks with Thatcher were effective.

Even better for the Adams Group, they now had a scapegoat to blame for the breakdown of any possible deal that would have delivered a settlement, and for explaining the prolonging of the hunger strike. The secrecy of their talks with Thatcher gave cover to both the British and the Adams Group, for reasons beneficial to each own’s agendas of self interest.

Late Afternoon

Left Hanging

By 4pm the ICJP were still waiting for the NIO official to come to speak to the prisoners. They were told ‘the official would be going in, but the document was still being drafted.’ Padraig O’Malley writes that “David Wyatt, a senior NIO official who had sat in on most of the discussions, rang to explain the delay: a lot of redrafting was going on and it had to be cleared with London”. At 6pm the ICJP contacted Alison again with concern; the Dublin government was also putting pressure on London to send someone in, to no avail.

Despair in the Dark

Danny Morrison, in his contemporary timeline, places this comm from Richard O’Rawe as a statement delivered late in the afternoon on Tuesday:

“We are very depressed at the fact that our comrade, Joe McDonnell, is virtually on the brink of death, especially when the solution to the issue is there for the taking. The urgency of the situation dictates that the British act on our statement of July 4 now.”

The prisoners would have been expecting the NIO to send an official in regarding the ICJP initiative that morning. They had been told by Adams that “more was needed” from the channel talks. They most likely did not know that it was those channel talks causing the delay; they definitely did not know that Thatcher was working on a draft that would have been acceptable to them.

Blanketman Thomas ‘Locky’ Loughlin describes the prisoners’ experience of the afternoon in the book, Nor Meekly Serve My Time:

[A]s it became clear [the ICJP] were making progress, we were led to believe by everyone except those most closely involved that a settlement was imminent. Even the Deputy Secretary of State Michael Alison indicated that the hunger strike was about to be resolved and that he would be sending in a message to wrap the whole thing up. This was the feedback most of us were getting at the time.

He continues,

“So morale was sky-high in the knowledge that it would soon be over and that no one else would die … it really appeared to us that it was over. … We felt like that because it seemed a settlement was really on the cards. The ICJP had been talking to the Brits for quite a while and to our knowledge were getting a very positive response. … [W]e knew that a messenger from the NIO was due in at any time with the necessary documents that would offer a solution.”

Evening

False Impression

By 7pm the Adams Group sent the first of two responses to Thatcher. She had extended an apology for ‘any false impression’ given by the ICJP’s initiative and taken the ICJP off the scene in response to the Adams Group’s complaints, and the breach of the confidentiality of the secret talks. The Adams Group, however, pressed on. It wasn’t the fault of the ICJP after all – it was the fault of the British: “If false impressions are given, they are contained in the very parameters set down by you”. The threat of closing off the channel discussions completely had upset them.

Shameless

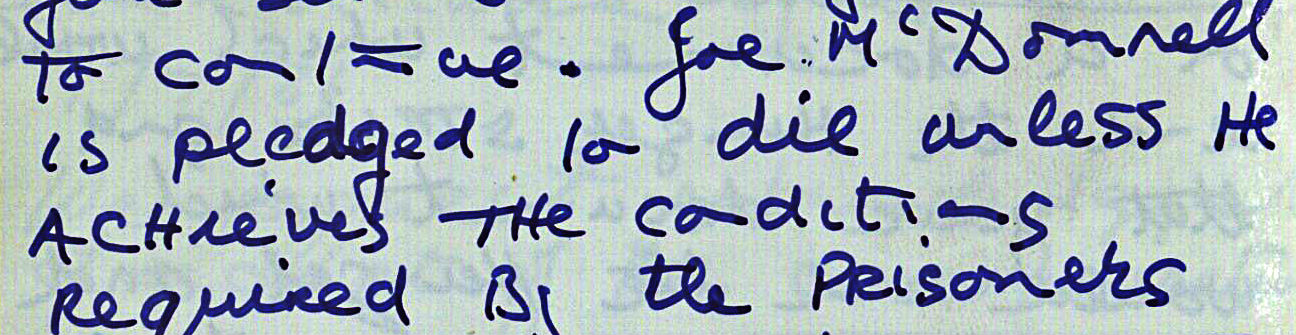

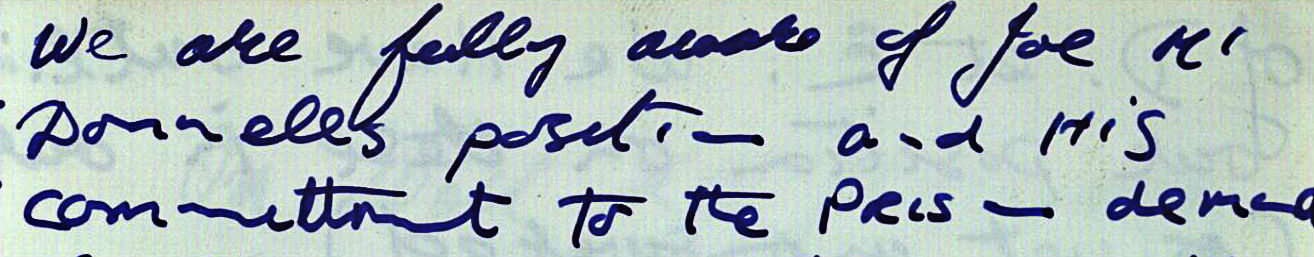

However, the Adams Group was no stranger to the art of brinkmanship, either. They held the impending death of Joe McDonnell over the end of their message, questioning the commitment of the British:

Does your last communication mean that you are breaking with the original criteria you set or do you wish to continue? Joe McDonnell is pledged to die unless he achieves the conditions required by the prisoners for a settlement.

Less than an hour later, a second, follow-up message was sent through the channel to Thatcher.

We are fully aware of Joe McDonnell’s position and his commitment to the prison demands. We have stressed this on many occasions. We cannot and will not intervene in the Hunger Strikes unless satisfied are met to their collective satisfaction.

The Adams Group were content to use Joe McDonnell’s commitment and the facade of the prisoners being in control as leverage – although the prisoners knew little to nothing of what was being done in their name, if they had any idea at all.

Tone Not Content

The Adams Group’s 3:30am rejection had been based on Remission, Work and Association; they were holding out for full remission, an emphasis on self-education, and wing visits. After hiding behind the condition and commitment of Joe McDonnell and the prisoners, they ended their evening communication settling for a ‘re-phrasing of D [Work] & E [Association]’.

Anger

The second communication asking for the rephrasing of Thatcher’s offer had been sent at 7:50pm. Immediately after sending off that message, according to Garrett Fitzgerald, at 8:30pm Danny Morrison and another person arrived without notice at the ICJP’s hotel, and ‘their attitude was threatening’.

Despite being told that as a result of their complaints the ICJP was now out of the picture, the Adams Group were angry and blamed the ICJP for endangering their secret talks:

“Morrison said their contact had been put in jeopardy as a result of the commission revealing its existence at its meeting with Allison; the officials present with Allison had not known of the contact.”

Morrison also demanded that the ICJP keep him informed of what they were doing, but the ICJP refused to cooperate. They viewed his visit as an ‘onslaught’.

Enough to Call Off the Strike

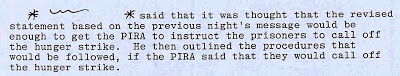

While Morrison was threatening the ICJP, the British were debating the draft settlement they were preparing to send. Earlier, Humphrey Atkins had sent a draft statement that retained a firm line. This was not the position Thatcher decided on going with, however; she continued to revise the offer sent down the channel at 11:30pm the previous evening.

If the Adams Group accepted the offer and ordered the hunger strikers to end the protest, ‘the statement would be issued immediately’. Otherwise, the British would revert back to their position of June 30th and their discussions with the ICJP. And if the Adams Group leaked anything about their secret talks again, the British would deny everything.

The British believed that their revised statement ‘would be enough to get the PIRA to instruct the prisoners to call off the hunger strike’ and had prepared the procedures that would follow once they did. Thatcher personally approved it all, the statement and the sequence, and directed the offer to be sent to the Adams Group.

Out of the Loop

The ICJP had no idea the extent of which they’d been sidelined, and continued to press Alison to send an official in to the prisoners. At 9pm Alison told the ICJP that someone would be going in shortly. Both Morrison’s timeline, which is based upon Ten Men Dead, and Garret Fitzgerald agree that by 10pm, Alison contacted the ICJP to tell them no one would be coming in that night after all, but that between 7 and 8 in the morning, an official would go in, and ‘this delay would be to the prisoners’ benefit’. Tellingly, when Alison was asked by the ICJP why no one had gone in yet, ‘Alison replied, “Frankly, I was not a sufficient plenipotentiary.”’.

Thatcher’s authority obviously superseded the NIO’s and her secret talks with Adams rendered the NIO-ICJP initiative pointless.

Bad Stick

That evening at 10pm, Bik McFarlane sends a comm out to Gerry Adams:

“…I don’t know if you’ve thought on this line, but I have been thinking that if we don’t pull this off and Joe dies then the RA are going to come under some bad stick from all quarters. Everyone is crying the place down that a settlement is there and those Commission chappies are convinced that they have breached Brit principles. Anyway we’ll sit tight and see what comes…”

Continued in Part Four: Wednesday 8 July 1981 ● Previously: Monday 6 July 1981

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.